Update on Journalism and Media Safety in Myanmar

A former journalist, who has been in detention since late December 2023, was sentenced to three years in prison for incitement in February 2024.

A documentary filmmaker, Shin Daewe, was sentenced to life imprisonment after her conviction on terrorism charges in January. This makes her the first female journalist and filmmaker to be given a life sentence since the Myanmar military’s illegal coup attempt on 1 February 2021.

A Rakhine-based former journalist, serving a prison sentence for incitement, was shot dead by two soldiers in the military headquarters of KaMaYa (378) battalion in Mrauk-U, western Rakhine state in January, 2024. Myat Thu Tun was among the seven detainees in the KamaYa (378) compound, where they had been brought to from the township prison. Their dead bodies were found by the Arakan Army after they captured the town after fighting military troops.

Two journalists were released in the first quarter of 2024. As of March 2024, 55 Myanmar journalists and media professionals remained behind bars. Ninety-one percent of the detainees are men, and the remaining 9% are women. Seventy-eight percent of the detained journalists are reporters or photojournalists.

The death of the Rakhine-based journalist brings to seven the total number of journalists who have died since the 2021 coup.

Cumulatively since the coup, 208 journalists and news workers have been arrested, 70 convicted, and 152 released under the military regime, according to the latest media monitoring data on the repression of journalists in Myanmar.

The armed conflict between Myanmar’s military and various ethnic armies and anticoup resistance groups has continued to spread, especially since anti-junta groups launched the Operation 1027 offensive in late 2023. In February, the National Unity Government’s foreign minister, Zin Mar Aung, said that the junta controls just 30-40 percent of Myanmar’s territory. The military junta called the State Administration Council (SAC), has also lost major regions along the border with China as well as Myanmar’s western border. Its military is also facing resistance in the eastern border, independent reports say.

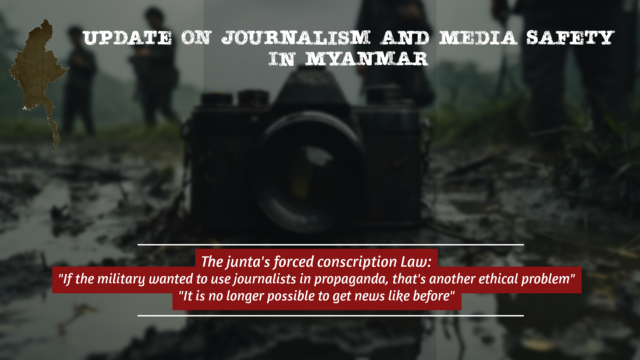

This situation is resulting in even more challenges for journalism work inside the country. Two issues stemming from the conflict situation are addressed in this report – increased armed conflict in Rakhine and journalists’ worries about the enforcement of the conscription law that the junta plans to implement from April onwards.

In Rakhine, the Arakan Army (AA) is on the verge of controlling the state after months of renewed fighting with the military junta since November 2023, media reports say. Violence has also led to the displacement and relocation of 100,000 people from Rakhine. The fighting has also pushed a number of journalists including at least one woman journalist across the border into neighboring Bangladesh. This is the first time that journalists have fled Rakhine to Bangladesh.

In need of military personnel given its losses on the battlefield, Myanmar’s military regime announced on 10 February that it would start enforcing the country’s military conscription law in April 2024. Under this law first enacted in 2010, men aged 18 to 35 and women aged 18 to 27 are required to serve in the military in an emergency situation. The junta has said women will not be drafted as yet.

The junta’s decision to implement the enforcement of the conscription law — widely regarded as illegal, without legitimacy and constitutes the forced enlistment of civilians — has added to journalists’ concerns for their safety and security. Like Myanmar citizens who are within the age ranges covered by the junta’s forced conscription, journalists in the major cities and areas of the country controlled by the Myanmar military are worried about being drafted into military service. On top of that, journalists worry that if the military finds out that someone is a journalist, that person could be forced to do propaganda too.

“If they were drafted by the military knowing that they are media experts and want to use them in military propaganda, there would be another ethical problem e.g. to write a blog or an article for the regime. Utilization of their media knowledge would be enforced,” a media expert said in an interview.