‘Unsung Heroes’: Myanmar’s Independent Journalists Vow to Continue Their Work

An artist’s take on the press freedom situation in Myanmar. / The Irrawaddy

After witnessing a junta military sniper shoot dead an elderly man who was trying to protect his grandchild while she retrieved a doll in Yangon’s Hlaing Thayar Township on March 14, 2021, freelance photojournalist Ko Aung Aung resolved to steadfastly continue documenting the junta’s atrocities.

On that black day alone, junta troops fired wantonly into crowds of anti-coup protesters in Hlaing Tharyar Township, killing around 80 people and injuring many more

“We’d only seen such scenes in movies. The junta’s blatant brutality shocked me,” recounted Ko Aung Aung.

Covering the junta’s crackdowns as a photojournalist, he witnessed youths, including girls, being brutally beaten by regime forces.

“My aim was to expose the regime’s injustices through my photos. I wanted people worldwide to see the junta’s brutality. Documenting their atrocities is all I can do,” said Ko Aung Aung.

However, he was arrested along with the demonstrators he was covering at a flash mob protest in Yangon in December 2021, enduring severe beatings during interrogation.

“My suffering pales in comparison to others’. Some of the young detainees, aged 16 and 17, faced severe beatings. I heard their agonizing screams. Some were subjected to stun gun torture, while others were beaten while suspended,” shared Ko Aung Aung.

He further revealed that two of his roommates were tortured to death by regime forces at the interrogation center in Yangon’s Shwepyithar Township.

After a grueling 10-month trial, he was sentenced to three years in prison and released as part of an amnesty in 2024.

“I’ll continue as a photojournalist despite the risks. But, at this moment, I am unable to resume my work [due to safety issues],” asserted Ko Aung Aung, using a pseudonym to protect his safety.

Journalists cover junta forces’ crackdown on a peaceful protest in Yangon in April 2021. / The Irrawaddy

Soon after the coup, independent media organizations and their journalists became targets for the regime as they continued reporting on every movement of the junta, including its numerous lethal crackdowns on peaceful anti-coup demonstrations nationwide.

Since then, the junta has banned media companies, raided their offices and jailed their journalists. Some have been tortured to death in detention.

However, despite the risk of arrest, torture and execution, many journalists resolutely continue their work, determined to shed light on what is happening in the country under the military dictatorship.

Like Ko Aung Aung, female video journalist Ahla Lay Thuzar endured two days of severe beatings during nine days of interrogation at the junta’s notorious Yay Kyi Ai interrogation center in Yangon.

She became a target for the junta due to her livestream coverage of their brutal crackdowns on peaceful anti-coup demonstrations.

She escaped the junta’s initial attempt to arrest her, when regime forces raided her house in Yangon on May 1, 2021, though her journalist husband was detained. Fortunately, he was released some days later.

However, her luck ran out four months later when she was apprehended by regime forces during a reporting trip in Yangon on Sept. 1, 2021.

Narrating her harrowing experience, Ahla Lay Thuzar described being handcuffed and blindfolded upon arrest and immediately taken to the Yay Kyi Ai interrogation center.

“Without being questioned, I was beaten on my thighs with bamboo sticks five times. It was so painful I barely noticed the rest of the torture,” she recounted.

Junta interrogators accused her and her colleagues of “selling the country” and demanded to know how many US dollars she earned from her reporting, reflecting the regime’s disdain for independent media.

On Nov. 22, 2022 she was charged under Section 505(a) of the Penal Code and sentenced to two years in Insein Prison. She was released as part of an amnesty on Jan. 4, 2023.

“I came out of prison crying because I had to leave my fellow prisoners in the cells. They urged me to take care not to be arrested again, and to expose what was going on in the junta’s prisons,” she said.

In mid-March, she headed alone to Mae Sot, Thailand, to continue her profession. Some months later, she was reunited with her husband and daughter in the Thai town across the border from Myawaddy, Karen State.

“Before the military coup, I had decided I would leave journalism to run my own business. But the coup made me turn back to the journalist’s life,” Ahla Lay Thuzar said.

Her challenges did not end when she crossed the border, however; the family is living in Thailand illegally.

An artist’s rendition of a journalist being tortured by regime forces at a junta interrogation center in Myanmar. / The Irrawaddy

A foreign analyst with Freedom Rights Myanmar who recently helped the group produce an analysis report about press freedoms and the state of the media industry under military rule, told The Irrawaddy that press freedom had significantly declined since the coup, as the military sees the media as a serious threat to its ability to control the hearts and minds of the Myanmar people.

The military regime is violating international laws protecting the right to freedom of expression in every possible way, including censoring media, as well as violently attacking and illegitimately detaining journalists, he said. He pointed out that the junta has illegally amended laws to increase censorship of the media and punish journalists for doing their legitimate work.

“Media is the oxygen for the pro-democracy movement and every time a media outlet closes or a journalist is detained, the movement as a whole suffers,” he added.

He said Myanmar media organizations and journalists have bravely sought to expose the truth about life under the military regime, adding that it is vital that they continue to get the support they need to keep doing so—including more of the financial support they have received from generous donors who want the democratic revolution to succeed.

Another perspective comes from 52-year-old journalist Ko Aung Mya Than from Ayeyarwaddy Region’s Maubin town. While actively reporting on the anti-coup movement and evading junta arrest, he was approached by Lieutenant Colonel Naing Lwin, the head of a special junta unit tasked with arresting anti-coup activists and journalists in Maubin Township, with an offer to collaborate.

“Due to [fears for] my family’s safety, I came out of hiding and met him. I was tasked with reporting anti-regime activities three times a day via text message. Initially, I feigned agreement to avoid detention,” he explained.

Failing to complete the tasks he was assigned and struggling to relocate his family, he was arrested by force during a night-raid on his house in mid-May 2021. Savagely tortured by junta soldiers led by Lieutenant Colonel Thet Lwin Oo, the commander of Light Infantry Battalion 216, he was left incapacitated temporarily.

“I was beaten and tortured until I lay motionless on the ground, unable to stand. The junta soldiers themselves believed I would not survive,” recalled the journalist.

Two days later, he faced interrogation at the base of the junta’s Infantry Battalion 27. After a day, he was charged under Section 505(a) of the penal code and imprisoned in Maubin.

Released under a junta amnesty after three months, he was rearrested 10 days later without any reason being given. After another 10 days in detention he was released upon the recommendation of his ward administrators. Upon release, he chose to flee to Mae Sot alone, fearing that he would be arrested again and prevented from continuing his work as a journalist.

His foresight proved crucial, as regime officials later charged him under the Counter Terrorism Law. His home was seized, and his wife and child briefly detained. Later, he reunited with his family in Mae Sot. The journalist required medical treatment at a hospital there for one month for severe injuries to his kidneys, liver, heart, backbone and head, inflicted during the brutal torture by regime forces.

Despite memory issues due to his head injuries and difficulties paying for his medication, he remains resolute. “The junta continues its arbitrary killings of civilians and burning of homes. I will expose their injustice until my last breath. I will not abandon journalism,” Ko Aung Mya Than affirmed.

Since the 2021 military coup, the Southeast Asian nation has become one of the worst countries globally in terms of the number of journalists jailed, with 206 reporters detained including 31 women over the past three years, according to a recent report by the International Center for Not-For-Profit Law (ICNL).

Myanmar has also become the second-worst jailer of journalists after China.

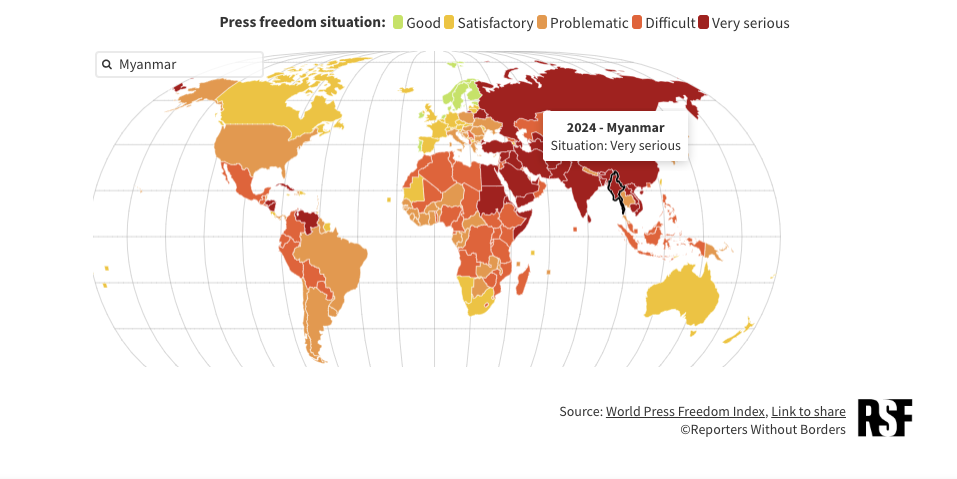

The Press Freedom Index of Reporters Without Borders (RSF), issued to mark World Press Freedom Day on May 3, ranked Myanmar 171st among 180 countries, saying it remains a dangerous place for journalists, who face a significant risk of being tortured, jailed and murdered.

An artist’s rendition of the execution of seven civilian detainees including a journalist by regime soldiers in Rakhine State in January 2024. / The Irrawaddy

Around 60 journalists are still behind bars, and so far at least five journalists have been killed by regime forces, according to international press freedom rights groups.

Ko Phoe Thiha, a journalist working for Western News

Ko Phoe Thiha was shot dead by regime forces along with six civilian detainees including a rap singer in the historic city of Mrauk-U in Rakhine State on Jan. 23, 2024 while being held at the junta’s Infantry Battalion 378.

The ethnic Arakan Army (AA) found their bodies buried in a bomb shelter after seizing the junta stronghold. Junta officials detained by the AA have confessed to involvement in the execution of seven Rakhine civilians.

Pu Tui Dim, co-founder and editor-in-chief of Khonmthung Media Group

Pu Tui Dim was tortured savagely by junta troops before being killed along with nine other civilian detainees in Matupi Township, Chin State in January 2022.

Before their executions, all victims were used as human shields by a military unit traveling in Chin State.

Ko Soe Naing, a photographer

Ko Soe Naing was detained together with another photographer while taking pictures of deserted Yangon in December 2021 while the whole country shut down as people joined a silent strike, staying at home to demonstrate their opposition to the junta.

The military regime later disclosed Ko Soe Naing’s death by asking their friends to retrieve his body from the military hospital in Yangon.

Ko Aye Kyaw, a photographer

Photographer Ko Aye Kyaw, who covered anti-regime protests following the coup, is believed to have been tortured to death within hours of his abduction by regime forces from his home in Sagaing Town, Sagaing Region on July 30, 2022.

A Sai K, an editor at Federal News Journal

The news editor was killed after being hit by junta artillery explosives while covering civilians fleeing a clash between regime forces and anti-regime resistance forces in Myawaddy Township, Karen State on Dec. 25, 2022.

Junta persecution

The ICNL report found that the junta has charged detained journalists with crimes under nine separate laws, mainly those dealing with incitement and publishing “false news”, while also weaponizing counter-terrorism provisions.

The junta’s sham courts have ignored domestic and international law and disregarded due process, jailingthe journalists for long terms of up to 20 years.

Reporters Without Borders (RSF)’s 2024 World Press Freedom Day Index / RSF TOPICS: Media, journalism, press freedom, human rights, military junta, crime

Soon after the military staged a coup in 2021 by overthrowing the democratically elected civilian government, the junta revoked the publishing licenses of independent media outlets and raided their offices without offering any reason.

Several independent media organizations—including The Irrawaddy—have been forced to continue their operations from exile.

Only those media outlets with close ties or links with the junta are allowed to maintain operations inside the country. A few foreign media outlets have also been allowed to continue operating inside the country.

However, risking death, arrest and detention, many journalists are secretly working inside the country, said Nan Paw Gay, the editor-in-chief of the ethnic Karen Information Center and the chair of the Independent Press Council Myanmar (IPCM).

“There is a lot of concern for their safety. Because it is very dangerous for them working inside,” she added.

Ko Banyar is one of the journalists clandestinely operating in Myanmar. Despite the looming threat of arrest, torture, and even execution, he remains resolute in pursuing his profession amid the oppressive grip of the military regime.

“Reporting on the ceaseless atrocities perpetrated by the junta against civilians nationwide, I frequently find myself plagued by dreams of being pursued or apprehended by regime forces,” shared Ko Banyar, reflecting on the toll working as a journalist in the current environment has taken on him.

As a man whose age makes him “eligible” for forced recruitment into the military now that the regime has newly activated the national conscription law, he must now also grapple with this threat.

“I won’t abandon my profession as a journalist, particularly in these challenging times under the military dictatorship. It’s our duty as journalists to illuminate realities unfolding in the country, to bring light to every instance of injustice,” insisted Ko Banyar (a pseudonym used for his safety).

U Toe Zaw Latt, secretary of the IPCM, emphasized that journalists are facing unprecedented insecurity.

“Journalists truly are unsung heroes,” he added solemnly.