UNICEF and partners expand mental health services for children and young people

©UNICEF Myanmar/2021/Nyan Zay Htet

” Little Pyit Tine Htaung” programme

Hlyan Htet, 6, keeps close to his mother these days and does not venture far. “I have friends, but my best friend is a dog from downstairs. We play every evening together,” says Hlyan Htet.

Although Hlyan Htet’s innocent charm shines through, his mother, Hnin Hnin, says the events of the past two years have taken their toll on him. “I was having problems in my marriage, then the first wave of COVID-19 came, and then the current crisis unfolded, one after the other.”

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted Hlyan Htet’s early education and socialization. At first, “Mommy taught me at home,” Hlyan Htet says. Fortunately, Hlyan Htet has access to the Internet and he is still excited by his lessons offered online via Zoom.

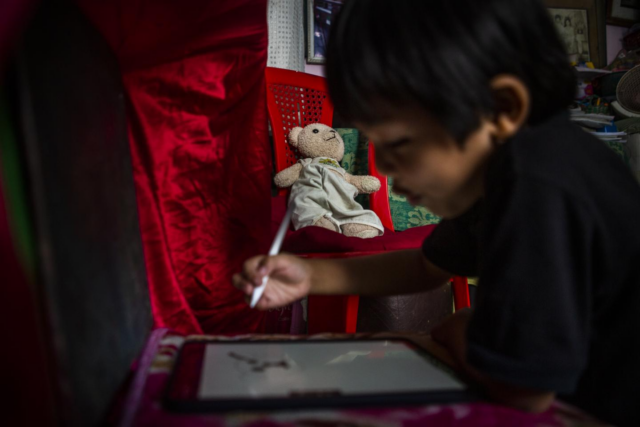

“I also love drawing,” says Hlyan Htet.

©UNICEF Myanmar/2021/Nyan Zay Htet Hlyan Htet demonstrating what he learned from ” Little Pyit Tine Htaung” programme.

However, the distressing circumstances of last year’s events has had a huge impact on Hlyan Htet. “My son started having trouble controlling his emotions and became overly attached and clingy to me. He gets up with me, since he doesn’t want to be left alone in bed, and, even when I pray, he sits beside me,” recalls, Hnin Hnin.

Hlyan Htet is not alone in his distress and behavioural response to these compounding situations. COVID-19 has left 12 million children out of school for over a year and the current crisis is further undermining their mental health and psychosocial well-being. Many have witnessed violence and attacks, and some have been victims, leaving them mentally, if not physically, scarred.

In response, UNICEF and its partners have been expanding psychosocial services for children and young people. This includes individual counselling, peer-support groups for adolescents and young people, and a national mental health and psychosocial advice helpline for children which is available in several ethnic languages.

In July 2021, Hlyan Htet started participating in one of the virtual psychosocial activities, Little Pyit Tine Htaungs, named after one of Myanmar’s traditional brightly coloured egg-shaped toys that always stand upright when thrown.

©UNICEF Myanmar/2021/Nyan Zay Htet In the evening, Hlyan Htet helps his mother in watering the plant.

Hnin Hnin found this service on the Facebook page of Metanoia, UNICEF partner and mental health services and resource centre in Yangon. One of Metanoia’s staff explains the process. First, virtual helpline operators register participants and explain the activities on offer. Children over the age of 7 fill in pre-assessment and post-assessment forms, or a caregiver fills in the forms on their behalf if the child is under the age of 7. The three-day sessions are adapted to three age groups: 4–12 years, 13–17 years and 18–29 years. The younger children “learn to understand emotions and empathy, respect and boundaries, and identity while doing arts and crafts activities,” says the Metanoia staff member, while the older age groups focus on “understanding reactions to crisis, practising stabilization techniques, promoting a sense of safety, maintaining hope, staying connected and strengthening efficacy to overcome crisis.”

After group sessions, participants are usually offered a counselling session. “We request parents to give them [their children] personal space during these sessions. We will then talk with parents, and sometimes we find it’s them who needs therapy, not their child,” says the Metanoia staff member.

Hnin Hnin says, “It’s really great and I’ve been recommending it to everyone.” She says that single parents, like her, are struggling with raising children during these times of crisis.

“This project definitely helped them and their children.”

Both Hlyan Htet and his mother also received individual therapy sessions from a counsellor. “He got close to the counsellor,’ says his mother. “He was even asking me about her since he dreamt of her.” After some sessions, “he has gained more control (over his emotions), except that he won’t let me disappear from his sight,” says Hnin Hnin.