‘We have no hope in Myanmar’ – A rebel and a journalist in love and on the run

In late July, anti-junta forces captured Mogok, Myanmar’s world-renowned ruby-mining town in northern Mandalay Region, marking an expensive loss for the overstretched military.

In the mountainous surroundings of “the valley of rubies,” source of the blue sapphire and coveted “pigeon-blood” ruby, Khayra and Thu Rein met, both 25, each forging their own path of resistance to the coup regime.

Choosing love

Khayra, a citizen journalist for a local media outlet, was forced into hiding in March 2021 when authorities issued an arrest warrant for her reporting under Myanmar’s Counterterrorism Law, which is widely used to silence voices critical of the junta.

Myanmar is second only to China as the world’s biggest jailer of journalists, according to Reporters without Borders.

Fleeing from her family home to the jungle, where resistance forces operate away from the military’s power centres, the journalist met her now husband Thu Rein, a rebel fighter with the People’s Defence Force (PDF)-Mogok.

While under the command of the publicly mandated National Unity Government, Thu Rein and his comrades were trained by the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA), a powerful ethnic armed group. The Ta’ang, or Palaung, are one of northern Shan State’s larger ethnic minority groups.

The TNLA jointly led the large-scale anti-junta offensive dubbed Operation 1027, the second phase of which began in late June, alongside the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army and the Arakan Army.

Within the PDF-Mogok, Thu Rein rose to the rank of deputy platoon commander, leading a group of men in guerrilla attacks against police stations and other junta targets.

“I joined the PDF to defy injustice by standing with the people. That’s the reason I picked up arms,” he told Myanmar Now.

However, as the couple sheltered together amidst bombardment from junta troops, Thu Rein realised that to commit to Kharya he would need to leave his position in the revolution, which he had been embedded in for 10 months.

“I told my mother I would only come back when I had achieved victory. But I fell in love,” he said, adding, “I cannot even describe how hard it was to make that decision.”

Thu Rein said he believes that by supporting Khayra to carry out her journalistic work, he continues to play a part in politics.

When asked how he felt about Mogok’s capture, he said, “I am very happy and proud of my comrades and brothers.”

Though the former soldier misses the camaraderie of life in the PDF, Thu Rein acknowledges that return is now an impossibility since the birth of the couple’s son.

Thu Rein also describes the difficult demands of the armed revolution, where he faced ammunition shortages, constant military offensives, and the loss of friends and colleagues.

Despite his choice to lay down arms, Thu Rein’s comrades approved of his decision, suggesting that the couple are always welcome back, he said.

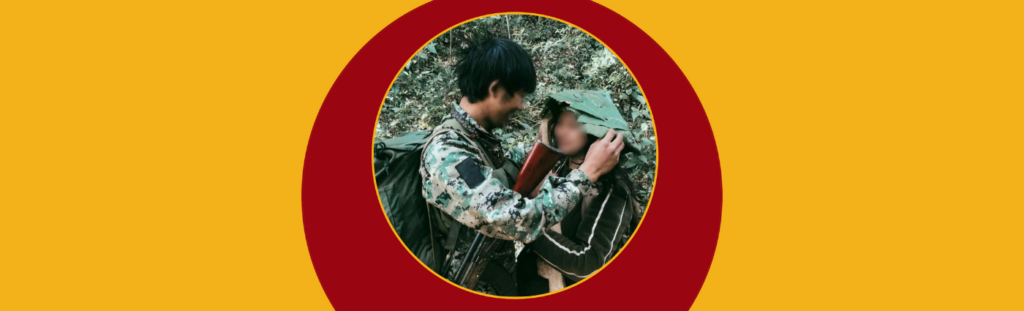

Khayra and Thu Rein together in a resistance-controlled area in northern Mandalay Region (supplied)

Running a race

Following the coup, the couple remained inside the country for three years, frequently on the move to avoid airstrikes or being found by military officials.

After leaving the jungle, the young family took up rented accommodation in Mogok, giving them a modicum of safety for their child, then one year old.

However, in February 2024 when the junta activated a long-dormant conscription law, the possibility of being detected by authorities heightened as officials increased their household inspections.

In addition to the risk of imprisonment and torture she faced as a journalist, if caught, Khayra faced a three-year jail term for being married to a former rebel.

“We had no choice but to run for our kid’s future,” she said.

As danger approached their door, the couple decided to leave Myanmar for neighbouring Thailand, where many Burmese journalists and dissidents have fled in fear of the junta’s persecution.

By the time Myanmar Now spoke with the couple, they had been in Thailand for five months. The family of three live in a small apartment, where Khayra works as a journalist for a Myanmar news agency, which she does not name for security reasons.

As Khayra works from home, Thu Rein, a former PDF fighter, takes care of their child and household responsibilities, while also looking for employment.

Though Thailand provides some respite from conflict, as undocumented migrant workers the couple face the threat of crackdown by the Thai police, which could mean deportation back to Myanmar or a hefty fine, both of which would be disastrous for the family.

“I am experiencing the same level of fear as in Myanmar, worrying if the police will find me in my home,” Khyara told Myanmar Now.

Living in Thailand without legal status or sufficient income, the couple have considered what a return to Mogok would mean now that the town has been liberated from military rule.

TNLA troops in 2023 (PSLF/TNLA)

The reality of return

While the capture of Mogok by the TNLA and its allies is a significant milestone for the anti-junta movement, the development does little to pave a way home for the young family.

Returning to Mogok, Thu Rein as a former PDF commander from the Ta’ang ethnic group would be required to serve in the TNLA.

“There was a glimpse of hope that we might be able to go back home,” said Khayra, “but it is not possible.”

In February 2024, the TNLA passed a mandatory enlistment law requiring all able-bodied youth between the ages of 16 and 35 of Ta’ang ethnicity to serve in the army—taking one family member from each household.

The TNLA has between 8,000 and 10,000 soldiers stationed in northern Shan State.

“If I go back, they would certainly come for me as I was also part of the revolution,” Thu Rein said. “They come with guns to collect soldiers. Families are left helpless with many difficulties,” he added.

“If something happened to me, it would be like losing a leg for my family.”

As a return to Myanmar would likely mean separation, the couple choose to remain in exile even if it means living precariously on a meagre income. Khyara earns just 100 Thai baht per story, the equivalent of less than three US dollars.

“We have to try to survive here because in Myanmar, we do not have hope,” she said.

“I feel like we are tiny blades of grass trying to survive while being pressed down by surrounding stones.”

For Khayra, her son and his future drive her forwards. “I absolutely do not regret any of my decisions because I stood for the right thing,” she said.

“However badly they might want to punish me, all I want to do is continue this job to report and tell the truth.”

*Names in this story have been changed for security reasons.