Schools Under Attack : Challenges to the right to education in Southeast Burma (June 2023-February 2024)

10 July 2024

Introduction

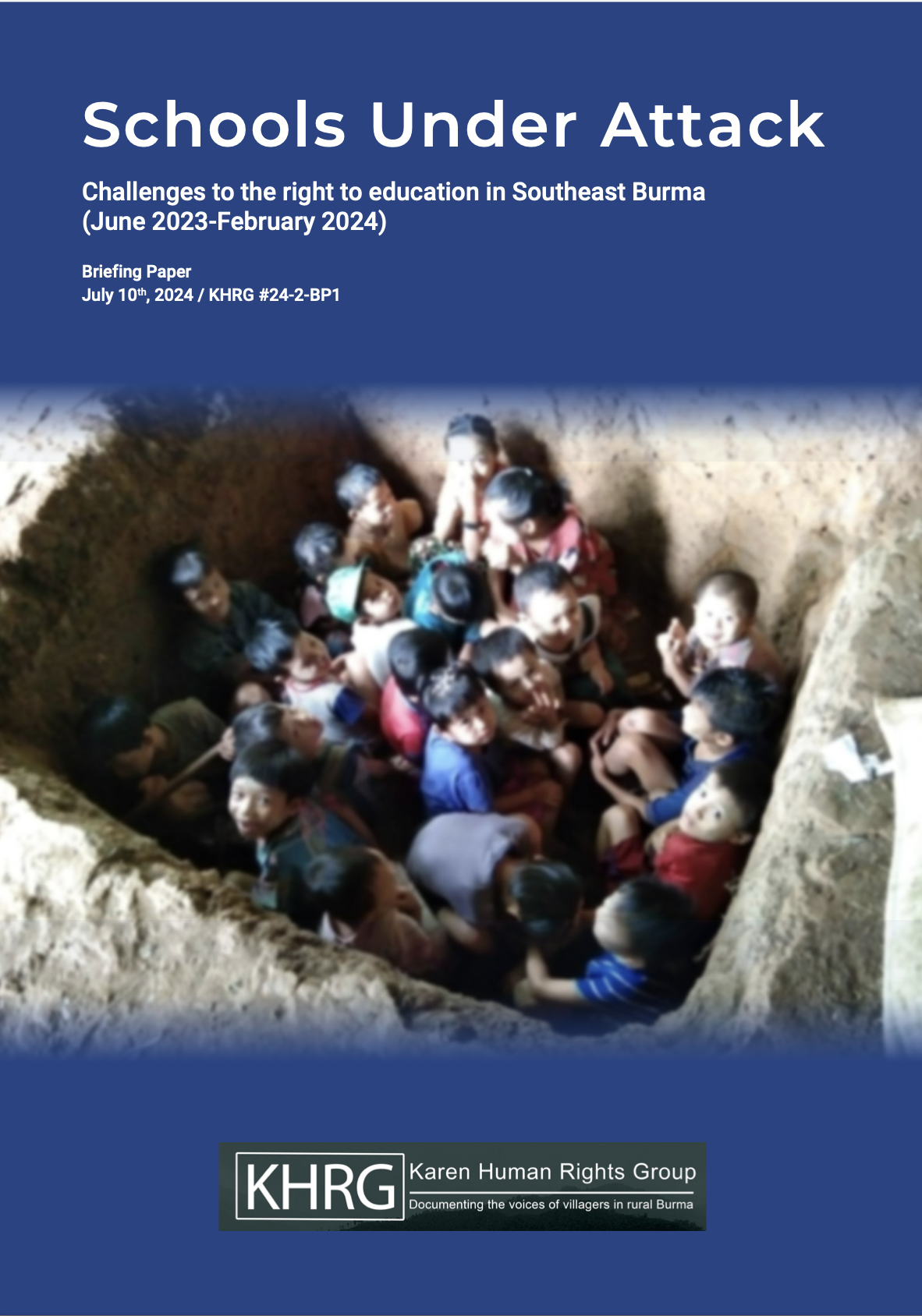

Villagers in Southeast Burma (Myanmar)[1] have been fighting for the right to teach and learn in accordance with their own culture for many decades, as Karen culture has been subjected to control and suppression by the Burma Army and government. Since the 2021 coup,[2] this situation has escalated, and Southeast Burma is facing a dire education crisis, where the rights of children are violated, schools are unsafe, and gross violations of human rights and humanitarian law are impacting every aspect of villagers’ lives. Children in locally-defined Karen State[3] need safe spaces to learn and access to quality education, parents and villagers need support to be able to sustain their children’s schooling, and communities and local leaders need help in their efforts to set up safe study centres.

This briefing paper presents evidence documented from June 2023 to February 2024, the most recent academic year in Burma, outlining the different challenges faced by villagers during the ongoing conflict, and the effects on education in Southeast Burma. The first section provides a brief overview of the situation of the right to education in the region before the 2021 coup, and the violations that have increased since then. The second section presents testimonies regarding the lack of access to education, as well as the challenges and risks that villagers face by attempting to address educational needs in their communities. The third section provides a security and legal analysis of the situation, as well as a set of policy recommendations for local and international stakeholders.

Contextual overview

Historical context: the situation of human rights in Burma

Human rights violations in Southeast Burma are directly linked to policies enacted by the Burma Army as early as the 1960s. One of these policies is the ‘four cuts strategy’, and its main purpose to destroy the links between insurgents, their families, and local villagers by cutting off food, funds, intelligence, and recruits to armed resistance groups.[4] Through this policy, the Burma Army has committed gross human rights abuses with total impunity against villagers in Karen State for decades, including threats, arrests, torture, indiscriminate firing of weapons, burning villages, destroying food, medical supplies and other property, restrictions to freedom of movement and forced relocation of civilian populations. Such violations may amount to war crimes and crimes against humanity.

In some areas of Southeast Burma, the signing of the preliminary Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA)[5] in 2015 resulted in an improvement in the human rights and economic situation. These included freedom of movement, increased livelihood opportunities, a heightened sense of security and safety, access to education, and freedom expression. However, villagers in Southeast Burma still faced travel restrictions, physical punishments and landmine contamination.[6] These improvements were also perceived by many Karen villagers as a means of Burmanisation.[7] For instance, there were more schools in mixed-control areas, but the curriculum taught often did not include the Karen language or Karen cultural education. Until 2014, teaching ethnic minority languages in schools was prohibited across Burma; demonstrating the use of education as a central tool in nation-building.[8]

Education system(s) in Southeast Burma

Before the 2021 coup, there were two primary types of formal education systems in Southeast Burma: schools under the Burma government administration; and schools under the Karen National Union (KNU)[9], administered by the Karen Education and Culture Department (KECD).[10] The KECD was founded in 1956 due to the Burma Army’s continuous practice of Burmanisation, with the purpose of preserving the cultural identity of the Karen peoples.[11]The main focus of the KECD curriculum has been on Karen language, culture, history and traditions.[12]

Between the 2015 NCA and the first year after the 2021 coup, there were five types of schools operating in locally-defined Karen State: (1) KECD schools; (2) Burma government schools; (3) self-funded/private schools; (4) religious schools; and (5) schools under cooperative administration between the Burma government and local KNU authorities, with mixed curriculums. In the latter, management roles were typically filled by Burma government teachers and the teaching of Karen language and history was limited.

Access to education since the 2021 coup

Since the 2021 coup orchestrated by the Burma Army and the establishment of the State Administration Council (SAC)[13], systematic human rights abuses have increased in Karen State, affecting civilians’ lives. Pressing amongst villagers’ challenges is access to education. The COVID-19 pandemic already forced many schools to close their doors.[14] Since the 2021 coup, schools have been constantly attacked, and because of this, many could not re-open or had to close down. Schools remain under threat of attacks and destruction as a result of the ongoing armed conflict and generalised violence. In addition, the recently enacted 2010 People’s Military Service Law on February 10th 2024 caused hundreds of young people in Karen State to flee their homes under threat of forced recruitment, in essence also interrupting their education.[15]

Since the 2021 coup, there are only four different types of schools for children and youths in Southeast Burma, and two different curriculums: (1) KECD schools; (2) SAC-run schools; (3) self-funded/private schools; and (4) religious schools. There are no more schools under cooperative administration. The first, third and fourth types of schools are located in KNU territory, apply the KECD curriculum, are granted recognition from KNU, and do not have the SAC’s recognition. The second type of school can be found in SAC and mixed-control territories (mostly in towns), apply the SAC curriculum, and operate without any cooperation with the other types of schools.

Announcements

28 February 2025

Asian NGO Network on National Human Rights Institutions , CSO Working Group on Independent National Human Rights Institution (Burma/Myanmar)

Open letter: Removal of the membership of the dis-accredited Myanmar National Human Rights Commission from the Southeast Asia National Human Rights Institution Forum

Progressive Voice is a participatory rights-based policy research and advocacy organization rooted in civil society, that maintains strong networks and relationships with grassroots organizations and community-based organizations throughout Myanmar. It acts as a bridge to the international community and international policymakers by amplifying voices from the ground, and advocating for a rights-based policy narrative.