Myanmar: Military onslaught in eastern states amounts to collective punishment

31 May 2022

AFP via Getty Images

- Post-coup military assault in Kayin and Kayah States includes war crimes and likely crimes against humanity

- More than 150,000 displaced, with entire villages emptied and burned

- Amnesty International interviewed almost 100 people and visited border area

Myanmar’s military has been systematically committing widespread atrocities in recent months, including unlawfully killing, arbitrarily detaining and forcibly displacing civilians in two eastern states, Amnesty International said today in a new report.

The report, “Bullets rained from the sky”: War crimes and displacement in eastern Myanmar, found that Myanmar’s military has subjected Karen and Karenni civilians to collective punishment via widespread aerial and ground attacks, arbitrary detentions that often result in torture or extrajudicial executions, and the systematic looting and burning of villages.

The violence in Kayin and Kayah States reignited in the wake of last year’s military coup and escalated from December 2021 to March 2022, killing hundreds of civilians and displacing more than 150,000 people.

“The world’s attention may have moved away from Myanmar since last year’s coup, but civilians continue to pay a high price. The military’s ongoing assault on civilians in eastern Myanmar has been widespread and systematic, likely amounting to crimes against humanity,” said Rawya Rageh, Senior Crisis Adviser at Amnesty International.

“Alarm bells should be ringing: the ongoing killing, looting and burning bear all the hallmarks of the military’s signature tactic of collective punishment, which it has repeatedly used against ethnic minorities across the country.”

Alarm bells should be ringing: the ongoing killing, looting and burning bear all the hallmarks of the military’s signature tactic of collective punishment, which it has repeatedly used against ethnic minorities across the country.

Rawya Rageh, Senior Crisis Adviser at Amnesty International

Post-coup surge in violence

For decades, ethnic armed organizations in Myanmar, including in Kayin and Kayah States, have been engaged in struggles for greater rights and autonomy. Fragile ceasefires in place in both states since 2012 broke down after the February 2021 coup, and new armed groups have emerged. In its operations, the military has relentlessly attacked civilians.

Some attacks appear to have directly targeted civilians as a form of collective punishment against those perceived to support an armed group or the wider post-coup uprising. In other cases, the military has fired indiscriminately into civilian areas where there are also military targets. Direct attacks on civilians, collective punishment, and indiscriminate attacks that kill or injure civilians violate international humanitarian law and constitute war crimes.

Attacks on a civilian population must be widespread or systematic to amount to crimes against humanity; in Kayin and Kayah States, they are both, for crimes including murder, torture, forcible transfer, and persecution on ethnic grounds.

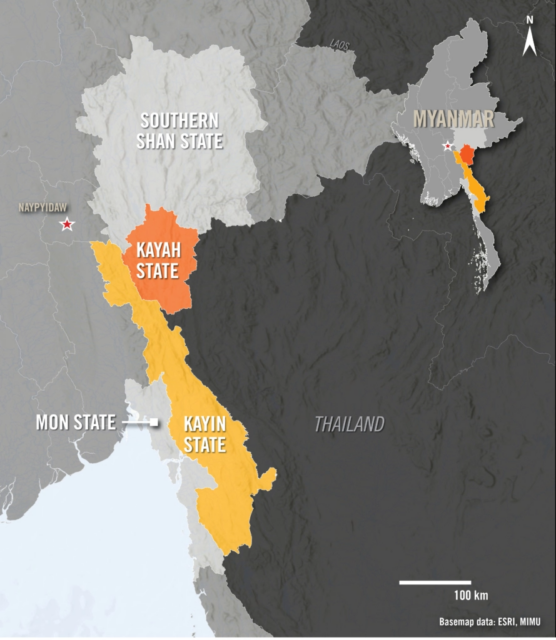

An overview map of Myanmar highlighting Kayah and Kayin States.

Unlawful strikes

In its ongoing operations, Myanmar’s military has repeatedly fired explosive weapons with wide-area effects into populated civilian areas. Dozens of witnesses told Amnesty International about barrages that lasted days at a time. The organization documented 24 attacks by artillery or mortars between December 2021 and March 2022 that killed or injured civilians or that caused destruction to civilian homes, schools, health facilities, churches, and monasteries.

For example, on 5 March 2022, as families were at dinner, the military shelled Ka Law Day village, Hpapun Township, Kayin State, killing seven people, including a woman who was eight months pregnant. A close family member of four of the people who were killed said he had to sit in his house all night looking at the bodies, for fear of being injured by further shelling, before burying them in the morning.

Many people described the military’s use of fighter jets and attack helicopters as particularly terrifying. Witnesses described not being able to sleep at night out of fear of air strikes, or fleeing to seek shelter in bunkers and caves.

Amnesty International documented eight air strikes on villages and an internally displaced persons (IDP) camp in eastern Myanmar in the first three months of 2022. The attacks, which killed nine civilians and injured at least nine more, destroyed civilian homes and religious buildings. In almost all documented attacks, only civilians appear to have been present.

In one case, at around 6pm on 23 February 2022, a fighter jet fired on Dung Ka Mee village, Demoso Township, Kayah State, killing two civilian men and injuring several others. Amnesty International interviewed two witnesses and a relative of one of the deceased as well as an aid worker who responded after the attack. They said there was no fighting that evening and that the nearest armed group base was a mile or more away.

A local resident, a 46-year-old farmer who witnessed the attack, said the military aircraft made three passes, firing guns and a rocket:

“When that fighter jet was flying toward us in a nose-down position, I was numb… When they fired the rocket, I got myself together and realized I had to run [to a bunker]… We were shocked to see the dust and debris come towards us… There is a two-story building… The family lives upstairs and the downstairs is a mobile phone store. This building collapsed and it was also on fire.”

Another witness, a 40-year-old farmer, saw the remains of a neighbour’s body:

“We couldn’t even put them in a coffin, we put them in a plastic bag and buried them. People had to pick up the body pieces and put them in a bag.” In another incident, the military carried out an air strike on Ree Khee Bu IDP camp at around 1am on 17 January 2022, killing a man in his 50s as well as 15- and 12-year-old sisters.

We couldn’t even put them in a coffin, we put them in a plastic bag and buried them. People had to pick up the body pieces and put them in a bag.”

A 40-year-old farmer who witnessed an air strike.

Extrajudicial executions

The report documents how Myanmar’s military carried out arbitrary detentions of civilians on the basis of their ethnicity or because they were suspected of supporting the anti-coup movement. Often, detainees were tortured, forcibly disappeared or extrajudicially executed.

In one of many cases where soldiers extrajudicially executed civilians who ventured out from displacement sites to collect food or belongings, three farmers from San Pya 6 Mile village in Kayah State went missing in January 2022. Their decomposed bodies were found in a pit latrine around two weeks later.

The brother of one of the victims said he identified the men by their clothes and the state of their teeth. Soldiers fired on him and others as they tried to retrieve the bodies; they could only return to finish the burial a month later.

In a massacre that prompted rare international condemnation, soldiers near Mo So village in Kayah State’s Hpruso Township reportedly stopped at least 35 women, men and children in multiple vehicles on 24 December 2021, and then proceeded to kill them and burn their bodies. Doctors who examined the bodies reportedly said many of the victims had been tied up and gagged, bearing wounds suggesting they were shot or stabbed.

Amnesty International maintains that the incident must be investigated as a case of extrajudicial executions. Such killings in armed conflict constitute war crimes.

Witnesses also described Myanmar’s military shooting at civilians, including those attempting to flee across a river along the border with Thailand.

Looting and burning

Following a pattern from past military operations, soldiers have systematically looted and burned large sections of villages in Kayin and Kayah States. Witnesses from six villages reported having items including jewellery, cash, vehicles and livestock stolen, before homes and other buildings were burned.

Four men who fled Wari Suplai village, on the border of Shan and Kayah States, said they watched from nearby farmland as houses went up in flames after most villagers fled on 18 February 2022. They told Amnesty International that the burning went on for days, destroying well over two-thirds of the houses there.

“It’s not a house anymore. It’s all ashes — black and charcoal… It’s my life’s savings. It was destroyed within minutes,” said a 38-year-old farmer and father of two young children.

Amnesty International’s analysis of fire data and satellite imagery shows how villages were burned, some of them multiple times, in parts of Kayah State. The burning directly tracks military operations from village to village in February and March 2022.

A defector from the military’s 66th Light Infantry Division, who was involved in operations in Kayah State until October 2021, told Amnesty International that he witnessed soldiers looting and burning homes: “They don’t have any particular reason [for burning a specific house]. They just want to put the fear in the civilians that ‘This is what we’ll do if you support [the resistance fighters].’ And another thing is to stop the supply and logistics for the local resistance forces… [Soldiers] took everything they could [from a village] and then they burned the rest.”

© Free Burma Rangers

They don’t have any particular reason [for burning a specific house]. They just want to put the fear in the civilians that ‘This is what we’ll do if you support [the resistance fighters].’…[Soldiers] took everything they could [from a village] and then they burned the rest.

A defector from the military’s 66th Light Infantry Division.

The violence has caused the mass displacement of more than 150,000 people, including between a third and a half of Kayah State’s entire population. In some cases, entire villages have been emptied of their populations; at times, civilians have had to flee repeatedly in recent months.

Displaced people are enduring dire conditions amid food insecurity, scant health care — including for the conflict’s enormous psychosocial impact — and ongoing efforts by the military to obstruct humanitarian aid provision. Aid workers spoke of growing malnutrition and increasing difficulties in reaching displaced people due to the ongoing violence and military restrictions.

“Donors and humanitarian organizations must significantly scale up aid to civilians in eastern Myanmar, and the military must halt all restrictions on aid delivery,” said Matt Wells, Amnesty International’s Crisis Response Deputy Director – Thematic Issues.

“The military’s ongoing crimes against civilians in eastern Myanmar reflect decades-long patterns of abuse and flagrant impunity. The international community — including ASEAN and UN member states — must tackle this festering crisis now. The UN Security Council must impose a comprehensive arms embargo on Myanmar and refer the situation there to the International Criminal Court.”

“The military’s ongoing crimes against civilians in eastern Myanmar reflect decades-long patterns of abuse and flagrant impunity. The international community — including ASEAN and UN member states — must tackle this festering crisis now. The UN Security Council must impose a comprehensive arms embargo on Myanmar and refer the situation there to the International Criminal Court.

Matt Wells, Amnesty International’s Crisis Response Deputy Director – Thematic Issues

Methodology

The report is based on research carried out in March and April 2022, including two weeks on the Thailand-Myanmar border. Amnesty International interviewed 99 people, including dozens of witnesses or survivors of attacks and three defectors from Myanmar’s military.

The organization also analysed more than 100 photographs and videos related to human rights violations — showing injuries, destruction and weapon use — in addition to satellite imagery, fire data, and open-source military aircraft flight data.

Announcements

28 February 2025

Asian NGO Network on National Human Rights Institutions , CSO Working Group on Independent National Human Rights Institution (Burma/Myanmar)

Open letter: Removal of the membership of the dis-accredited Myanmar National Human Rights Commission from the Southeast Asia National Human Rights Institution Forum

Progressive Voice is a participatory rights-based policy research and advocacy organization rooted in civil society, that maintains strong networks and relationships with grassroots organizations and community-based organizations throughout Myanmar. It acts as a bridge to the international community and international policymakers by amplifying voices from the ground, and advocating for a rights-based policy narrative.