Military Atrocities and Civilian Resilience: Testimonies of injustice, insecurity and violence in Southeast Myanmar during the 2021 coup

24 November 2021

Since the February 1st 2021 military coup, the human rights situation in Myanmar has seriously deteriorated. The State Administration Council (SAC) headed by Senior General Min Aung Hlaing has engaged in systematic violence against civilians and stripped away the few key civil and political protections that the already problematic 2008 Constitution was supposed to guarantee, further opening the door for widespread human rights violations. The SAC’s treatment of citizens as enemies of the state and its unrelenting efforts to crush all opposition have resulted in widespread violence and the loss of lives during this first six months of the coup. The SAC has shot and killed peaceful protesters, bombed rural villages forcing thousands to flee, deprived people of access to health services and information, and turned the law against the people of Myanmar to arrest, detain, and torture at will.

As future returnees could potentially face similar In highlighting the human rights violations that have occurred since the February 1st coup, this report presents the degrading security situation and humanitarian crisis that civilians in Southeast Myanmar are currently facing. It also presents the hopes and struggles of rural villagers and civilians, to show how, despite the increased insecurity that they face, they continue to seek out ways to counter a military regime they know to be both illegal and unjust. Most importantly, this report seeks to ensure that the experiences and concerns of rural ethnic villagers are not just heard but addressed.

Overview

Interviews conducted by KHRG reveal the level of violence that the SAC undertook against protesters, and the ways in which protesters have continued to voice their opposition to the coup in the face of increasing brutality and repression by the state military. Protesters recounted stories of fear and insecurity as they encountered the ruthless response of the SAC to civilian opposition, yet equally expressed a strong sense of hope and an unwavering commitment to upholding the fight for democracy and freedom from oppression through to the very end. These interviews also highlight the efforts of civilians to support and sustain each other as protesters and those engaged in civil disobedience sought refuge and protection.

This report also presents the escalation of insecurity in rural ethnic areas, where the Myanmar military has long used violence against civilian villagers as a key strategy in waging war against ethnic armed actors. Although conflict and attacks had been ongoing in certain parts of Southeast Myanmar even prior to the coup, the shifts currently taking place reflect a complete disregard for human rights and signal a return to a “four cuts” approach that, as independent researcher Kim Joliffe has highlighted, “treats civilians not just as ‘collateral damage’ but as a central resource in the battlefield”. Although some areas in Southeast Myanmar have experienced little to no fighting, others have endured an ongoing onslaught of attacks and fighting since the coup. It is estimated that, as of June 23rd, close to 177,000 villagers in Southeast Myanmar, including 50,000 in Kayin State, have been displaced since the February 1st coup (with over 140,000 still experiencing displacement as of August 23rd). KHRG also received a growing number of reports of direct attacks on civilians, including targeted killings, forced labour, looting and confiscation. That, combined with the SAC’s use of the COVID-19 pandemic as an additional weapon of war, has left rural villagers at-risk from multiple forms of attack.

What is evident in both rural and urban areas is not just the increase in acts of violence since the coup, but that the SAC has sought to legitimise its own abusive actions and inscribe in law the deprivation of fundamental human rights. The Myanmar military, in ousting the newly elected civilian government, not only illegally seized power by making unsubstantiated claims about election fraud, but also set about instituting legislative changes that would effectively legalize state-based repression and its own use of excessive force against civilians.

Similarly, the SAC is using the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA) and calls for ceasefire to then give itself permission to undertake whatever measures it deems necessary to “keep the peace”. Although the SAC announced a unilateral ceasefire on its part since April 2021, it also stipulated that it would continue to respond to “actions that disrupt government security and administration”, thus authorizing its own military offensives. Since the coup, it has repeatedly accused other armed actors of failing to honor peace commitments, and to label any groups that oppose the SAC as terrorists.

From the outset, it has also used the COVID-19 pandemic, citing the Natural Disaster Management Law, to justify arrests. It has limited access to information about the health crisis, and more recently to vital medical care, using the pandemic as a political weapon against the public as well as ethnic armed groups.

With ongoing displacements, a worsening COVID-19 pandemic, and the SAC blocking national and international aid organisations’ access to critical areas, the humanitarian crisis has become dire, placing many in life-threatening situations.

Methodology

This report is based on interviews conducted with rural villagers as well as with participants in the protests and Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) who fled to KNU-controlled areas for their safety. KHRG began conducting interviews shortly after the February 1st coup, through the first week of June 2021. A total of 133 interviews were conducted, covering a wide range of topics related to the coup. Forty-nine of those interviews were with people who joined the Civil Disobedience Movement, many of whom had either fled to their home village in Southeast Myanmar or been provided refuge in a KNU-controlled area.

This report also draws on raw data reports prepared by KHRG researchers working in local communities within KHRG’s operational area. The raw data for this report covers the period from the beginning of February through the end of July, thus the first six months of the coup. Over 100 raw data submissions were used for this report.

Key Findings

Chapter 1: Protests

After the February 1st coup, protests erupted throughout Myanmar in both urban and rural areas, often drawing tens of thousands of people in large cities, and/or uniting hundreds of villages in rural areas, all voicing their opposition to the coup and military dictatorship. Although peacefully engaging in the right to freedom of expression, civilian protesters became the target of repression and violence at the hands of the military regime.

- Since the military overthrew the civilian government on February 1st 2021 and declared a state of emergency allowing for the transfer of all legislative, executive and judicial power to the Commander-in-Chief of the Defence Services, it has also instituted laws and policies that restrict or suspend the fundamental rights of citizens. In particular, it has enacted legislative changes that undermine freedom of expression, freedom of peaceful assembly and association, and the right to privacy. Although in contravention of international law, these legislative reforms, along with the declaration of a state of emergency, are specifically being used to silence and criminalise any and all forms of dissent.

- Despite the peaceful nature of the protests, SAC security forces cracked down on the protests using excessive violence, including brutally beating and torturing protesters as well as shooting at them using both rubber and live bullets. Hundreds of protesters have been killed and thousands more injured as a direct result of violence by SAC security forces.

“In joining the protests in Yangon and Mandalay, it is like we pick straws over who will die in the street [joining the protests is like a deadly game of chance]. They [police] can shoot people at any time if they want. In fact, they shot people. Many people have already died. They [police] never gave a warning to people before cracking down on the protests.” –Maung E—, a university student in Yangon

- KHRG conducted interviews with a number of SAC soldiers and police officers who had joined the Civil Disobedience Movement, and who confirmed the use of excessive force and violence by security forces during the protests. In some cases, this was violence that they had witnessed, but in other cases, it was violence that they were ordered to undertake as part of their security activities surrounding the protests.

“When there was a protest in Hledan, Yangon we would break up the mass gathering. There was a total of 50 of us. Six of us had real guns [machine guns] including me. We had to fire live rounds [against protesters]. Our bullets are not meant for shooting innocent civilians.” –A police officer based in Bilin Township, Doo Tha Htoo District

- As the SAC responded to the protests with increased violence, the protesters adopted more varied protest strategies and also developed self-protection strategies in an attempt to make themselves less vulnerable to injury, violence and arrest by security forces.

- SAC security forces have also engaged in arrests without providing the reason for the arrest and without allowing access to legal counsel or communication with family members. Likewise, family members and friends of detainees have often been unable to access information about why they were arrested, where they are detained, how they are doing, whether they are alive or dead and other critical information about court proceedings.

“Laws are from their mouth [decided solely by the SAC] because whatever they say is considered law [toward the civilians]; they can kill, they can arrest, they can detain and they can do whatever they want [by the order of SAC authorities]. There is no rule of law. Every action they have been practicing is against the civilians.” –A young teacher from Hpa-an Town

Chapter 2: The Civil Disobedience Movement

On February 2nd 2021, healthcare workers across Myanmar walked off their jobs to express their opposition to the military coup. This form of protest quickly spread to other branches of public service, eventually turning into a nationwide, large-scale Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM).

- While CDM participants in general spoke of the desire for democracy, a return to civilian government, and the hope of undermining the SAC by shutting down the wheels of government, SAC security forces (police and military) who joined the CDM also cited unjust and unlawful orders as motivating factors.

- The CDM participants with whom KHRG conducted interviews faced major barriers to joining the movement, making it clear that a decision to join could have life-threatening consequences. Since joining the CDM, participants have experienced livelihood issues, increased risks and restrictions, as well as threats of arrest and attack by the SAC against themselves and their family members, leading many to go into hiding.

“I also worry for my family’s security because of the actions that the Burmese military has done. If they cannot arrest me, they will target my family. I heard that they will threaten my wife. I heard that they will harm my family.” –A CSO worker from Ayeyarwady Region

- KNU local leaders have been attempting to provide security and necessities such as food, shelter, and clothing for CDM participants who have reached KNU-controlled territory, leading CDM members, protesters and human rights activists to flee to KNU territory seeking protection. Informal networks and local community support have also been particularly strong, with some civilians seeing this as their best way to contribute to the movement.

“Ordinary people like us do not need to participate in the CDM. We just have to support those who do participate in the CDM. The situation happening now is not right, so we have to support them. We have to care for them and we have to give them food, and support them in what they need. They are working for us as well.” –Saw Y— from Ta Naw Th’Ree Township, Mergui-Tavoy District

Chapter 3: Militarisation and a return to violence

The security situation in rural areas of Southeast Myanmar rapidly degraded during the first six months following the military’s seizure of power. Since the military coup, human rights violations have steadily increased, as have displacements and threats of injury and death to civilians in rural areas. Just the news of the military takeover led many villagers to begin preparing for the possibility of fighting, and thus displacement, and for the re-emergence of the kind of human rights abuses that they had suffered in the past.

“Some people dare not to stay at home anymore. They go to stay at their huts. Those who are living close to the road dare not to sleep at their houses. They heard that Tatmadaw soldiers will patrol so they are afraid and go to sleep in other places. Then, they come back to their houses in the morning. Some people hide food in the jungle. If anything happens, they can go and hide there and they will have food.” –A missionary in Dooplaya District

- Increased ground attacks in some areas began shortly following the military takeover but the airstrikes in Karen State, which began on March 27th, marked a pivotal moment in the escalation of fighting and attacks, and have contributed to a growing climate of insecurity that recalls earlier periods of military abuse.

- t is extremely difficult to estimate the total number of displacements due to conflict since the February 1st military coup. UNHCR, which is working on relief operations, estimated 47,700 in Kayin State, and another 1,100 in Mon State. The figures are likely much higher given the poor access to IDP sites and displacement information in many areas, and the variable nature of displacements, which can be recurring or extended, and can vary from several days to several months or longer.

- One of the biggest problems continues to be access to aid. Due to both COVID-19 and increased insecurity following the coup, many international stakeholders are no longer operating on the ground in some areas. Even attempts by local stakeholders to provide support to IDPs have met with opposition by the SAC.

“We will be shot dead so no boats dare to run. We dare not go to send rations for the IDPs. The supplies are accumulating on the Thai side. The boats from the Thai side do not go to the Myanmar side because they are afraid they will be shot by SAC soldiers.” –A boat driver interviewed by KIC

- While airstrikes and fighting have led to large-scale displacements and a growing humanitarian crisis, the human rights situation has also degraded with an increase in abuses (like forced labour, targeted killings, looting and arbitrary arrest) that had curtailed following the NCA.

- Areas that have faced less fighting and attacks have still been heavily affected by the overall climate of insecurity. Aside from witnessing the movement of troops and reinforcement of troops and supplies in their region, many villagers noted increased patrolling by armed soldiers.

- Another cause of concern for villagers in some areas has come from the emergence of various militia groups. Since the coup, the SAC has been appointing new members who are former Tatmadaw soldiers. They are rotating between different areas within the village tract, and have been appointed specifically to monitor the activity of villagers and the local KNU.

“We only dare to criticise the military coup secretly within our family because there are many junta spies that [report] people who criticise and disagree with the military government to the police.” –An interviewee from Dooplaya District

- Since the coup, there has been renewed insecurity and threats to freedom of movement for villagers. The military has been checking travelers and making arrests, which has increased fear surrounding travel.

- KHRG has received an increasing number of reports about landmine accidents since the military coup. Despite ongoing calls on the Myanmar government and all ethnic armed groups to halt the use of landmines and to accede to the Mine Ban Treaty, the planting of new landmines continues to take place.

Chapter 4: COVID-19 since the coup

The lack of testing and reporting by the Ministry of Health and Sports (MoHS) has not been able to conceal the fact that, as of early July, COVID-19 cases have skyrocketed and Myanmar is facing a serious humanitarian crisis.

- Since the announcement of the coup, KHRG has received multiple reports that most of the prevention measures that had been set up to protect villagers from the spread of the virus to rural areas were no longer being adhered to. The lack of accurate information about COVID-19 since the SAC took power has contributed to the sense that COVID-19 was no longer something villagers needed to be concerned about.

“Since the military coup, even in our village and at the national level, people didn’t continue thinking about COVID-19 anymore. I myself didn’t continue thinking about it anymore.” –A village secretary in Noh T’Kaw Township, Dooplaya District

- The SAC has not only continued to provide inaccurate information, it has also restricted access to resources and services, and prevented other key actors from helping manage the spread of the virus and address the health needs of the people of Myanmar.

- Prior to the coup, the NLD government had been working to acquire COVID-19 vaccines, and began making plans for rolling out vaccinations. Because it is now the military government taking over this process, rural villagers are refusing the vaccination due to distrust of the military.

“[W]e worry that the Myanmar military will mix something into the vaccine. […] So no one dares to get the vaccine.” –A villager from T’ Nay Hsah Township, Hpa-an District

Chapter 5: Challenges to peace, democracy, and development

The coup has had devastating effects on all aspects of daily life in Myanmar, creating impacts as individualised as lack of access to the internet and as widespread as a downturn in the national economy. By eroding possibilities for peace, democracy and development, these problems have touched the lives of all civilians, but have impacted rural villagers in particular ways.

- The coup involved not just a wider shift from elected civilian government to military dictatorship but also a replacement of local administrators with SAC-selected individuals. Replacing elected leaders with military-appointed ones not only serves to further undermine the democratic process, it erodes relationships of trust between local communities and the administrators that are supposed to serve and represent them.

“Everything depends on the village administrator, because no matter how much you protect your village, if the village administrator works under the military government you can’t do anything. He will simply send information to the SAC.” –A villager from Ta Naw Th’Ree Township, Mergui-Tavoy District

- The coup has had harsh impacts on Myanmar’s economy, at both the individual and national levels. Civilians across Southeast Myanmar are experiencing job loss, higher prices on necessities, restrictions on travel, and loss of access to telecommunication systems, all of which are increasing food and livelihood insecurity.

- The CDM has had a large impact on education in Southeast Myanmar. After the SAC seized power, many teachers in government schools joined the CDM, so most of the government schools have had to close. Even when the SAC reopened some government schools on June 1st 2021, there was a shortage of both teachers and students.

- There have also been heavy impacts on access to healthcare. There are approximately 30,000 physicians in Myanmar, and about 20,000 work for the government hospitals. As a response to the coup, approximately 75 percent of those working in government facilities have joined the CDM and refused to work.

“If people need to go for an operation and they are not allowed to go […] they will just die.” –Naw O— from Moo Township, Kler Lwee Htoo District

- The coup has also had an impact on access to information, through telecommunication interruptions and SAC control of news and media outlets. Telecommunication interruptions are particularly serious in rural areas where information is already limited to what people can access through their phone.

Chapter 6: Moving forward

- Although there may have been early confidence that the Spring Revolution would be successful, there have been increasing divides regarding how the fight should go on. Many stressed the importance of continuing the fight until the end, and the need for more government staff to join the CDM. Others noted the lives already sacrificed.

“People from Myanmar have died many times already. Therefore, we must not feel hesitation to die this time [for this cause]. If we are afraid to die this time [for this cause] and just do nothing about it [military dictatorship], our lives will be dead forever.” –An interviewee from Kawkareik Town

- For some, the coup has served as an awakening since it highlighted the oppression that ethnic minorities have faced at the hands of the military, as well as the level of violence the Myanmar military is capable of.

- In the eyes of many, a political solution involving negotiation with the military regime is not possible. Despite the sense that negotiation would not benefit civilians, some believe that the way forward is still through peaceful means. Others spoke of the necessity for well-planned self-defense and carefully executed offensives involving the collaboration of both the People’s Defence Force (PDF) and EAOs.

- Several interviewees highlighted the need for full inclusion of minority voices in any strategies and plans for moving forward. A strong emphasis was also placed on the need for a federal democracy that allows for self-determination as the only means of ensuring ethnic minority rights and equality.

“I protested for my country to be free from military dictatorship, for my country to become a real federal democracy and for the ethnic minorities to receive equal rights. If we don’t have equal rights in this country while we are living in this country, there is no reason we could consider ourselves citizens of Myanmar.” –A KECD teacher in Dooplaya District

Conclusion

Information continues to pour in regarding incidents of violence, with increasing stories of torture, forced labour and killings in rural Southeast Myanmar. Fighting and attacks continue and are becoming more widespread. Many facing displacement are still not receiving support, and some have reported having little left to eat. Displacements are ongoing and the possibility of seeking refuge across the border in Thailand remains limited. Reports of illness-related deaths are being submitted, yet villagers are unsure whether this is due to COVID-19 or some other illness, since there is little availability of testing or medical care.

Ethnic minorities want their voices to finally be heard, but also to be supported as they stand up for their own rights and for equality and justice.

“We have had [in the past] to solve whatever we face in our own way and suffer it by ourselves. Therefore, people think no one will stand with or for them when they have any problems or face anything. […] [I]t is critical that civilians feel that they are being supported by others, that they are not alone in this fight. They need others to stand with them and beside them.” –An interviewee in Kawkareik Town

Recommendations

To the State Administration Council (SAC)

- Immediately step down and hand over power to the National Unity Government (NUG).

- End the crackdown, arrests and targeted attacks on protesters and CDM participants.

- Cease the halting and seizure of medical and humanitarian supplies intended to alleviate the COVID-19 and other humanitarian crises in Southeast Myanmar.

- Reverse the suspension of Sections 5, 7 and 8 of the Law Protecting the Privacy and Security of the Citizens (Pyidaungsu Hluttaw Law No. 5/ 2017).

- Revoke amendments to the Ward or Village Tract Administration Law, the Penal Code and the Code of Criminal Procedure (SAC Law Nos 3/2021, 5/2021 and 6/2021).

- End interruptions to communication services and the suppression of media freedom since this is a violation of the right to access information.

- Cease attacks on civilian areas, as well as patrols and military transports through, in or near villages or livelihood areas; demilitarise areas close to villages and farms by removing troops and camps.

- Stop all forms of forced labour, including using villagers as human shields, porters, and navigators; and refrain from making arbitrary demands on local communities such as demanding the use of their vehicles, boats or other property for military purposes.

- End arbitrary and illegal taxation practices, as well as the confiscation of civilian property for military and personal use.

- Ensure compliance with international humanitarian standards and human rights law; and end impunity by ensuring that any armed actor who has violated the rights of any person is held accountable for abuses in fair and transparent investigations and judicial processes in independent and impartial civilian courts.

- Put an end to clearance operations, as well as activities, commonly termed the “four cuts strategy”, that prevent civilian access to food, communication, aid and other basic necessities.

To international organisations, NGOs, funding agencies, and foreign governments

- Refrain from giving any legitimacy to the military junta and from recognising them in any international forum.

- Exclude the SAC as a partner for the distribution of aid.

- Urge UN agencies in Myanmar to take a clear and strong position in responding to the situation on the ground, and to use all possible resources to limit the human rights abuses and violations undertaken by the SAC.

- Provide financial and technical support as needed for the NUG, including on international human rights laws and standards and other matters of governance.

- Consult and sign MoUs with the NUG and EAOs to address the unfolding humanitarian crisis across the country.

- Support a UN Security Council resolution on a global arms embargo.

- Diversify international funding distribution so that more funding is made directly available to non-state actors, particularly ethnic service providers and civil society organisations, regardless of their registration status.

- Prioritise methods of service delivery and communication that rely on local CSOs/CBOs and ethnic service providers that have the ability and networks (due to consistent access and trust from the community) for local implementation of support programmes.

- Recognize the complex logistics of service delivery and be willing to contribute to solutions proposed by local CSO/CBOs and ethnic service providers.

- Mitigate the impacts of displacement, armed conflict and insecurity on livelihood through increased support and initiatives that reduce the vulnerability of small farmers and day labourers.

- Support EHOs and other non-state health actors, both regarding COVID-19 prevention and treatment (including screening/testing and the running of quarantine facilities), and the provision of other essential health services in rural areas.

- Urge Myanmar’s neighbours to ensure that their authorities do not deny entry to people crossing the border seeking refuge; and encourage them to work with cross border organisations to develop support and protection services for those seeking refuge.

- Provide neighboring countries with the necessary resources and technical assistance to provide humanitarian aid, including for COVID-19, for the people from Myanmar who are fleeing the military violence.

- Engage with Myanmar’s neighbours to ensure the passage of aid to Myanmar, in particular through cross border aid organizations and local civil society organizations already operating in the area.

- Advocate for the release of political prisoners, including political actors, protesters, activists, human rights defenders, journalists and their family members.

- Insist that the Security Council refer Myanmar to the ICC or set up an ad hoc tribunal to ensure all perpetrators of genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and mass atrocities are prosecuted and that justice is attained for victims and survivors.

To the SAC and EAOs/EAGs

- Put an immediate halt to the planting of landmines and ban all further use of landmines; mark all areas contaminated by landmines and unexploded ordnance (UXO), and inform the local communities of these locations for their safety.

- Comply with international humanitarian standards and human rights law, particularly with regard to the protection and safety of civilians.

Gallery:

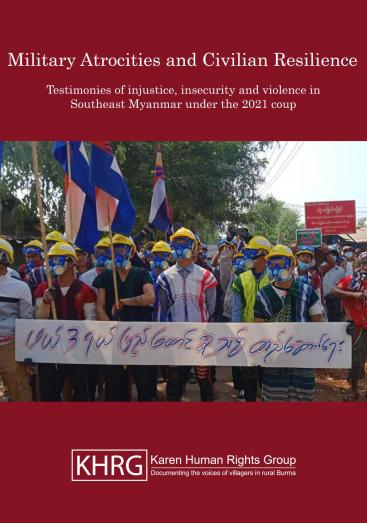

This photo was taken on March 22nd 2021. It shows a demonstration during which 500 villagers from four different village tracts (T’Hkaw Pwa, Way Shweh, Koh Nee, and Noh Nya Lar) gathered and held a protest against the military coup. They started marching at T’Hkaw Pwa village and went around to Aaw Law See, Way Shweh and Kyun Pin Seik villages in Plaw Too area, Moo (Mone) Township, Kler Lwee Htoo District. The protest specifically claimed to be an “all ethnic group” protest. [Photo: KHRG]

KHRG received this photo on March 8th 2021. Around 1,000 local villagers from K’Moh Thway village tract, Ler Doh Soh Township, Mergui-Tavoy District held a protest against the military junta [the date of the protest is unknown]. The protesters were accompanied by KNLA soldiers, who were there to protect them from violence by SAC security forces. [Photo: Local villager]

This photo was taken on March 9th 2021 on the Asia Highway near Kawkareik Town, Aw Hpa Hpa Doh village tract, Kaw T’Ree Township, Dooplaya District. It shows some of the protective gear that protesters began using in order to shield themselves from SAC violence during the protests. [Photo: KHRG]

This photo was taken in April 2021 in Day Bu Noh village, Pay Kay village tract, Lu Thaw Township, Mu Traw District. It shows the destruction of villagers’ houses and belongings as a result of SAC airstrikes on March 27th 2021. [Photo: KHRG]

This photo was taken in April 2021 in Bu Noh village, Pay Kay village tract, Lu Thaw Township, Mu Traw District. It shows an unexploded high explosive (HE) bomb that was dropped during the SAC airstrikes on March 27th 2021. [Photo: KHRG]

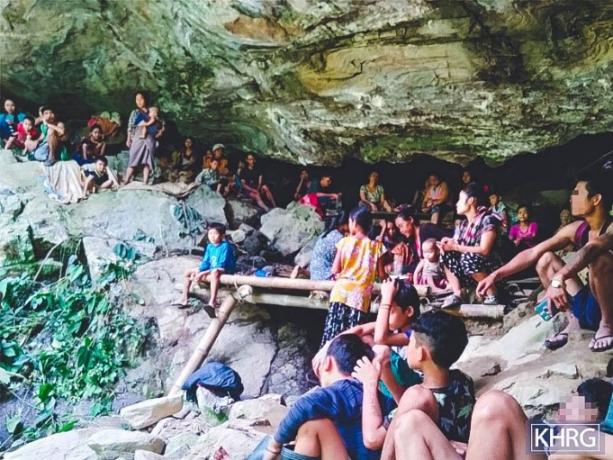

This photo was taken on April 28th 2021 in Kw— village tract, Bu Tho Township, Mu Traw District. It shows villagers, including children, who were displaced and hiding in a cave to protect themselves from the SAC military fighter jets that dropped bombs on the area on April 27th 2021. [Photo: KHRG]

This photo was taken on April 11th 2021 on the Thai side of the Salween River. The villager in the photo is one of the IDPs hiding in the forest. This old man is over 100 years old, and is ill. He is covered by a dirty blanket and lying on a thin mat. No one was able to take care of him as his wife was also very old. A few weeks later, he passed away. [Photo: KHRG]

This photo was taken on April 25th 2021 in Ce— village, Ce— village tract, Thandaunggyi Township, Toungoo District. When SAC LIB #730 took security for the road, SAC soldiers entered villagers’ houses and asked them for food. Villagers complied out of fear that the soldiers would do something bad to them. [Photo: KHRG]

This photo was taken on March 1st 2021 in Kt— village, Kheh Kah Hkoh village tract, Ler Doh Township, Kler Lwee Htoo District. It shows the body of one of two victims who died in a landmine explosion on March 1st 2021. [Photo: Local villager]

Download for Full Report in English.

Download for Full Report in Burmese.

Download for Briefer in English.

Download for Briefer in Burmese.

Download for Briefer in Karen.

Announcements

21 May 2025

Open letter: Malaysia must lead ASEAN with principle, not hypocrisy, to address the Myanmar crisis

Progressive Voice is a participatory rights-based policy research and advocacy organization rooted in civil society, that maintains strong networks and relationships with grassroots organizations and community-based organizations throughout Myanmar. It acts as a bridge to the international community and international policymakers by amplifying voices from the ground, and advocating for a rights-based policy narrative.