‘LIFE IS AT A TURNING POINT’: INSIDE MYANMAR’S RESISTANCE

28 June 2021

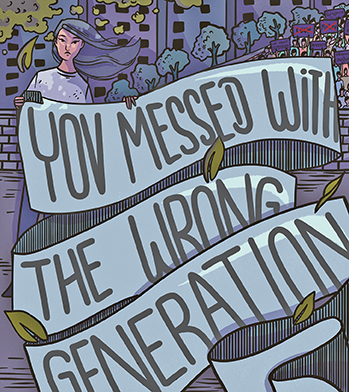

Illustration: Raven

Four people on the frontlines of the anti-coup movement in Myanmar tell Preeti Jha why they are not giving up.

THE DOCTOR

Than Oo* stopped working on 3 February 2021. Instead of driving to Mandalay General Hospital, as he has done nearly every day for 15 years, he took to the streets. Thousands of medical workers across Myanmar did the same. Their mass walkout in protest against the coup marked the start of a nationwide Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) that has brought public services to a virtual standstill.

‘It was a really difficult decision,’ said the 40-year-old. ‘I had to leave my patients.’ As it is, he was contending with the lingering fallout of previous junta rule. There was a time, he remembers, when patients arrived for operations carrying their own surgical equipment. By starving the healthcare system of funds, the generals had decimated it. Even after budgets grew, out-of-pocket payments for medical treatment in Myanmar soared and remain one of the world’s highest. ’I won’t let [dictatorship] happen again. We have to stop it – especially for our next generation.’

Speaking to me on the Signal app in a video call from an undisclosed location, Than Oo looked fatigued. His grey-streaked hair, which he normally cuts short, fell to his shoulders. He was growing a beard for the first time. He and his wife, also a doctor, have been forced into hiding as striking doctors are wanted criminals in junta-ruled Myanmar. ‘Many of my colleagues have been charged,’ he said. Hundreds of other doctors, nationwide, are on the run too.

Than Oo turned to organizing rallies. But it was impossible to stop being a doctor. He treated former patients at a private hospital for around a week before the generals threatened the clinic with closure. ‘Now I have to treat my patients secretly,’ he says.

Every morning, seven days a week, Than Oo runs an underground clinic. There are a handful operating across Mandalay. At first his makeshift site got by mostly with tele-consultations. Doctors reached patients who had access to a fixed-line internet connection, even as most of the population was forced offline after the military blocked the internet on mobile phones. But when the protests grew and state violence intensified, this wasn’t enough.

‘The crackdowns felt like battlefields,’ he said, describing how doctors formed mobile clinics near protest sites for emergency care. ‘Some were shot in the chest. We inserted emergency tubes. But at that time there were few doctors or facilities, so we lost tens of patients.’

The doctors mobilized. Through donations from Mandalay residents, less than two months after the coup, they opened a 100-bed hospital. ‘We made it in a secret place. We have three operation theatres,’ said Than Oo. Two ordinary cars, fitted with basic trauma equipment, function as ambulances.

One patient he can’t forget is an 18-year-old shot on three separate occasions. ‘The first time was in February – he saw his girlfriend die, she was shot in the head. He ran with her body and a gunshot wound to his abdomen.’ It didn’t stop the teen going to protests. The next time he was shot in his right forehand. When Than Oo saw him, he bore a wound on his right thigh. The team ‘repaired the [torn] artery. But unfortunately we needed to amputate the right leg.’

The hospital where Than Oo previously worked is now a military base. Like thousands of others in the CDM, the doctor has drawn no salary since January. ‘I know I have a very high chance of being arrested. But I have to fight till the end.’

Illustration: Raven

THE ACTIVIST

‘Let me see,’ she says, counting on her fingers, ‘this is the ninth safe house since the coup.’ But Thinzar Shunlei Yi went on the run months earlier. As a prominent democracy activist, she was already in the military’s crosshairs. While freedoms emerged under Aung San Suu Kyi’s leadership, dissent against the army or government could still land activists, journalists and ordinary citizens in jail.

‘The previous transition period was fake,’ says the 29-year-old plainly. ‘It’s all collapsed. But I take it as a positive because now we’re going for a real revolution against the military dictatorship.’

The days leading up to the first protests, she says, were agonizing. ‘We took a week to get on the streets because we were aware of the capability of the military. They’re not like the police or the military in other countries. They have been killing innocent civilians in Rakhine, in Kachin, in Shan. We knew they would do this at some point.’

It was with courage, then, but also some hesitation that she led her first march to Sule Pagoda, the golden temple in downtown Yangon that has shimmered over earlier uprisings. The first swathe of protests were huge and energizing. ‘Almost every day thousands and thousands of people flooded the streets, the bridges. In that moment I felt we were all united.’

But her worst fears soon materialized. On 9 February, Mya Thwate Thwate Khaing, 19, was shot in the head by security forces during a peaceful demonstration in the capital Naypyidaw. She died after 10 days on life support, the first protester to be killed post-coup. The movement got stronger. ‘We were chased like cat and mouse,’ kettled into streets for hours, forced to hide in alleyways, says Shunlei, of rallies in Yangon. ‘They used stun grenades, sometimes they shot rubber bullets to scare us. We looked out for snipers.’ Around 30 of her friends have been detained. She says all have been physically or sexually abused.

Protests, though smaller, still go on. ‘We’ve kept the momentum going… But it’s hard to keep people on the street,’ says Shunlei, explaining how they’ve shifted to flash mobs and other guerrilla tactics. In March she was added to the warrant list, now running into the thousands and including actors, social media influencers and journalists. She left Yangon at around the same time. ‘They can’t arrest all of us at once so I feel kind of relaxed.’

Unlike most people I’ve interviewed in recent weeks, Shunlei wanted to use her real name. ‘My voice is my last defence of my free speech,’ she says.

Illustration: Raven

‘Many of my colleagues have been charged. Hundreds of other doctors, nationwide, are on the run too

THE ARTIST

Shein* was born in 1988, seven months before a mass pro-democracy uprising crushed by the military. Growing up under the shadow of the generals, when Myanmar was largely isolated and free speech muzzled, graffiti offered an outlet for expression. As a teenager she joined a crew that scaled Yangon’s walls after dark to mark their dissent, united in their hatred of junta rule. But when the National League for Democracy was elected to power, she stopped. ‘I didn’t want to destroy the street any more,’ Shein said. ‘Now they [the military] have come back, so we have to go back.’

Her art is a call to action. But in the initial confusion that engulfed the February coup she urged restraint. On day one, she drew a cat, inspired by a revolutionary Burmese poem, telling people to stay home. Next, she created a ‘keyboard fighter’ to marshal people ‘to spread the message’ on social media. By day six, pent-up anger burst onto the streets. In Shein’s pictures, bold women stared back, raising sarongs or pots in defiance. They took new life on stickers and vinyl posters held aloft at protests. In the evenings she unfurled banners across city flyovers with the movement’s rallying cry: ‘You messed with the wrong generation.’ They were always gone by the next morning.

‘We weren’t afraid,’ said the 33-year-old, pausing when the din of Yangon traffic – quieter than usual according to Shein – overpowered her voice. Protest art has a long history in Myanmar’s democracy movement. Slogans, memes and illustrations have spread wildly online, buoyed by new campaigns such as Raise Three Fingers. Artists like Shein have also been inspired by the tactics of the Milk Tea Alliance – a term coined by protesters in Hong Kong, Thailand and Taiwan last year referring to the drink popular in all three places. Myanmar is a core part of the alliance now as activists see their political struggles as shared in a new era of protests fuelled by online imagery.

Illustration: Raven

Fewer people are protesting outdoors these days, said Shein, but resistance art still lights up pockets of Yangon from time to time, serving to empower as well as heal. ‘A lot of my poet and musician friends have been arrested,’ she said. But Shein wants to remain in Yangon, where she’s focusing on commercial work to raise funds. ‘We need to support our brothers and sisters,’ she said, of those in the CDM. ‘I think I am safe for now.’

THE MP

Crickets hum in the background. The internet connection breaks so often we resort to exchanging voice messages. From a jungle training camp in Myanmar’s borderlands, a newly elected MP explains why he has taken up arms.

‘They gave me 24 hours,’ said Mo Htet*, a bookish 33-year-old, about the ethnic armed group he joined in late February. ‘So I decided very quickly. We need a new army to protect our people. Because our army is destroying them.’

Like a growing number of anti-coup protesters he now thinks armed resistance is vital to creating a federal democracy. Wearing black-rimmed square glasses, his hair razed short, Mo Htet radiates conviction and sadness at the same time. ‘I got married during the pandemic. It was a very new, a very fresh family,’ he begins. In November he was elected to parliament for the first time. ‘I was energized, ready to serve my people.’

Instead he found himself by their side, protesting on the streets. He watched as 23 of his constituents were shot dead, with many more wounded, at peaceful anti-coup rallies. Like the hundreds of people now reported to be joining ethnic armies in Myanmar, the massacres catalyzed his decision. ‘They are not an army, they are not police, they are a terrorist group,’ he said of the security forces.

Speaking from his military base, Mo Htet describes his routine. The day begins at 4.00am with drills in the dark. Mosquito and scorpion bites are a new norm. Food is rationed. In March the former social worker held a gun for the first time. ‘I never dreamed that I would have to practise shooting. It feels like life is at a turning point.’

Mo Htet doesn’t reveal which ethnic army he has joined. There are some two dozen different groups that have been battling the Tatmadaw for decades. But now the National Unity Government, set up by Myanmar’s ousted civilian leaders in April, says it is bringing them together to form a federal army to fight the junta.

Some have raised doubts over whether disparate factions could ever unite, or challenge the powerful Tatmadaw even if they did. Mo Htet thinks they can. Every anti-coup protester I spoke to saw a role for armed resistance – most for the first time – alongside a democracy struggle long powered by nonviolent resistance.

‘Even though we don’t have battle experience, we can learn the strategies. We believe we can combine as a federal army to fight together. We believe we will win,’ he said.

In late February Mo Htet left home without telling a single family member where he was going – hoping that would offer them some protection. It wasn’t enough. They too have gone into hiding, expecting arrest, as the authorities hunt for him.

‘There are two types of MPs in my country,’ says the new soldier. ‘One is trying to fight, the other is behind bars.’

*Names changed to protect identities.

Original Post: New Internationalist

Announcements

28 February 2025

Asian NGO Network on National Human Rights Institutions , CSO Working Group on Independent National Human Rights Institution (Burma/Myanmar)

Open letter: Removal of the membership of the dis-accredited Myanmar National Human Rights Commission from the Southeast Asia National Human Rights Institution Forum

Progressive Voice is a participatory rights-based policy research and advocacy organization rooted in civil society, that maintains strong networks and relationships with grassroots organizations and community-based organizations throughout Myanmar. It acts as a bridge to the international community and international policymakers by amplifying voices from the ground, and advocating for a rights-based policy narrative.