“Attack the Enemy”: Chin Guerillas Hunt Down Myanmar Troops

23 June 2021

When the Myanmar military started killing peaceful protesters in remote Chin State in the wake of the 1 February coup, local youths armed themselves with handmade rifles and started shooting back. They say they have killed at least 165 soldiers.

By Author Athens Zaw Zaw Illustrator Charis Loke

One evening in late April, a group of young men crouched in the wooded hills overlooking a narrow mountain road outside the town of Mindat, in Myanmar’s Chin State, waiting for the enemy to arrive. As expected, a large truck and three smaller vehicles rumbled up the road carrying soldiers and military equipment. As soon as they came into striking distance, the men in the hills opened fire.

“We attacked them with bombs first, and we shot them with handmade rifles,” says Salai*, a leader of the Chinland Defence Force. The militia formed in the wake of Myanmar’s 1 February coup to protect the residents of Chin State—a mountainous, underdeveloped region bordering India and Bangladesh—from military violence.

Amid the explosions and gunfire, Salai says he heard the Myanmar soldiers shout: “These men are really doing it! Attack them back!”

The battle continued into the night. Eventually, Salai and his comrades decided they had inflicted enough damage and fled back into the hills. They stayed awake and kept watch until morning in case of a counter-attack. They were relieved when they realised every CDF member had come back alive, and they learned later that they had killed three Myanmar soldiers and wounded seven.

“That [battle] was a first for all of us,” Salai says. “We didn’t have much experience before, but we did it. We became confident.”

In the weeks since, the CDF have mounted several more attacks against the Tatmadaw, as the Myanmar military is known, in Mindat and throughout Chin State, scoring further victories but also suffering heavy losses. Vastly outgunned, their continued operations show the lengths many Myanmar civilians are willing to go to resist military rule.

“I think their actions show the desperation of the people in Chin State, and all over Myanmar, who have suffered for many years at the hand of the Myanmar military,” says Steve Gumaer, president of Partners Relief & Development, which has been providing emergency supplies to displaced civilians in Chin State.

“Reports that we have heard are that many people feel like they tried peaceful protests, and in response, many have been killed, so now they are taking up arms to fight for their freedom.”

Childhood War Games

In the immediate aftermath of the coup, Salai had no intention of taking up arms against the military. A husband and father of two children, he previously worked in the development sector in Chin State, whose predominantly Christian, ethnic Chin population have long resisted pressures to assimilate into Myanmar’s Buddhist, ethnic Bamar majority. Like many other Mindat residents, Salai spent the weeks following the coup joining peaceful protests against military rule.

But after Tatmadaw soldiers began shooting protesters in Mindat in mid-February, he and other locals—students, workers, farmers and hunters—started making plans to form a group to protect their families and neighbours from violence and detention. They officially established the Chinland Defence Force on 4 April and established chapters in all nine of Chin State’s townships.

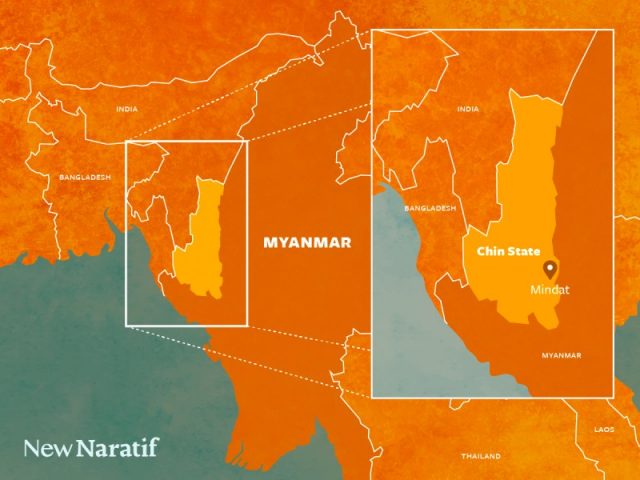

Map of Myanmar, showing the location of Mindat in southern Chin State. Graphic: Ellena Ekarahendy

On 24 April, Tatmadaw forces arrested seven young protesters in Mindat who were demonstrating in support of the National Unity Government, a government in exile formed by deposed lawmakers. CDF members reached out to military authorities to try to negotiate the detainees’ release.

“We urged the junta forces to release our peaceful civilian protesters. They promised at first to release them back to us, but they did not keep their promise and kept detaining them. So we fought their forces,” Salai says.

News of the CDF’s modest victory against the Tatmadaw spread on social media, earning praise among anti-coup activists across the country, some of whom have formed local “people’s defence forces” in their own neighbourhoods.

The CDF mounted several more guerilla attacks on the Tatmadaw over the following weeks. On 26 April, they allegedly attacked a police convoy near a golf course outside Mindat, killing one security officer and injuring three, according to Myanmar state media. Despite being less well armed than the state security forces stationed across Chin State, the CDF have a few key advantages: knowledge of the rugged terrain, local hunting traditions and access to small explosives and handmade rifles known as tumi, both of which are commonly used for hunting in Chin State.

“When we were young, we used to pretend to fight the enemies in this mountainous terrain,” says Pau Pu*, a musician from northern Chin State whose friends and relatives have joined the CDF. “These battles are very similar to our childhood play scenarios.”

“[The junta forces] could potentially attack our towns at any time, but the CDF can surely attack them in the jungles, where they have to pass to reach the towns,” Pau Pu says.

“They tried peaceful protests, and in response, many have been killed, so now they are taking up arms to fight for their freedom.”

The Chin militia scored its greatest victory on 14 May, when they destroyed six military trucks as they were heading toward Mindat.

“We waited and attacked them on the way,” Salai says. “We had more experience than before, and we arranged the attack properly. We seized the six trucks and took the guns and bullets from there.”

Myanmar state media reported that the attack was carried out by “about 1,000 rioters with guns and homemade mines, causing six vehicles [to be] destroyed by fire, and some soldiers were killed and disappeared”.

The CDF claims to have killed 165 Myanmar soldiers and suffered 30 of their own casualties as of 10 June. Nine civilians have also been killed in the fighting. Security forces have killed more than 850 civilians nationwide since the coup and detained more than 6,000.

“We don’t need to learn much about the geography, as we have learned it since childhood. …We know how to use bombs and our handmade rifles,” Salai says. “If the Burmese soldiers don’t use heavy guns and airstrikes, they will never win against us.”

“Punishment and Revenge”

On 13 May, the day before the attack on the six-truck convoy, Myanmar’s ruling junta, known as the State Administration Council, declared martial law in Mindat.

State media reported that the junta would set up a military tribunal “to try perpetrators of the terrorist attacks and those who encouraged the violence and crimes” in the Mindat area.

Then, on 16 May, Tatmadaw forces began shelling the town and cut off its water supply the following day, sending thousands of residents fleeing into the surrounding forests and hills. Apparently wary of CDF attacks, the Tatmadaw began shuttling in reinforcements by helicopter to raid and loot local residents’ homes.

A local Chin worker for an international humanitarian organisation describes the “brutal retaliation” carried out by the junta forces.

“There was the indiscriminate firing of live bullets at protesters, door-to-door searching of houses, and torture and intimidation. Four civilians who protested peacefully were shot, and one succumbed to his injury. Many protesters were warned and also sent to prison. Parents were afraid that their daughter’s dignity and honour would be robbed,” the relief worker tells New Naratif.

The Tatmadaw’s use of rape as a weapon against civilian populations has been well-documented, including by a 2019 UN Fact-Finding Mission who reported that sexual violence by security forces has been “part of a deliberate, well-planned strategy to intimidate, terrorise and punish a civilian population”.

The relief worker says these measures are “punishment and revenge” for the casualties local militias have inflicted on the Tatmadaw in Chin State.

“When we were young, we used to pretend to fight the enemies in this mountainous terrain. These battles are very similar to our childhood play scenarios.”

A month since the imposition of martial law, Mindat is a ghost town; 90% of the population of around 25,000 has fled, and pigs and dogs are now roaming the town. More than 8,000 displaced people are taking refuge in 18 camps around Mindat. The few residents who failed to flee before the army took control of the town are now trapped inside, where they avoid leaving their homes and risking interrogation by Tatmadaw troops.

As the people fled Mindat, the CDF followed to protect them.

“We watched the area, and we provided security for them,” Salai says. “The refugees are now in the jungle, in the villages, in the churches, in the monasteries. They face shortages of food, health problems and accommodation problems. We have never faced such misery before.”

Although CDF resistance appears to have resulted in the townspeople’s displacement, the militia still receives support from the people of Mindat, according to Salai.

“The local people have been struggling with the crackdowns by the Burmese soldiers, so it is hard to ask for their support, but we are still getting support from them,” Salai says. “We don’t have many things to eat in the jungle, so people make us snacks of corn and sweets. …If things were stable, the people in the town would cook food and send it to us.”

Gumaer, of Partners Relief & Development, says the CDF’s popular support comes in spite of the risk of aiding what the Tatmadaw see as terrorism.

“It does sound like they have the support of the people,” he says. “The people in Chin State are well aware of the Myanmar military tactics, and would know that any action they take could result in indiscriminate and overwhelming violence.”

“A Duty We Cannot Refuse”

The CDF are not the first non-state militia to arise in Chin State. In 1988, local leaders formed the Chin National Front to fight for self-determination for Chin people against the military regime that ruled Myanmar at the time. But the group has been largely inactive since signing a ceasefire agreement with Myanmar’s nominally civilian government in 2012.

In late May, the Chin National Front signed an agreement with Myanmar’s shadow National Unity Government to “demolish the dictatorship and to implement a federal democratic system”. But they have not taken up arms against the junta, partially necessitating the formation of the CDF.

However, Salai says the new militia does not seek to replace its predecessor, as its purpose is different from the many ethnic armed organisations that have been fighting for self-determination in Myanmar over the last several decades.

“We need to learn from [existing] ethnic armed groups for better [tactics], but the main reason why CDF exists is to protect people and to attack the enemy if they mistreat our civilians. We are not dealing with political dreams—we are protecting our people,” he tells New Naratif.

“If the Burmese soldiers don’t use heavy guns and airstrikes, they will never win against us.”

Col. Naw Bu, spokesperson for the Kachin Independence Army, which has been at war with the Tatmadaw for 60 years, says the CDF could benefit from cooperation from older, larger ethnic armed organisations.

“They are fighting with their hunting knowledge right now, but war is different from hunting,” the colonel tells New Naratif. “If they get proper training from ethnic armies, it will be better.”

CDF members agree, and they have reached out to other ethnic armed groups for future cooperation.

In the meantime, however, Salai and his comrades are stuck in the wilderness outside Mindat. He has not seen his family for three months, but he receives news about them from his friends.

“It hurts whenever I hear that my kids miss me, but defending our people is a duty we cannot refuse,” he says. “The CDF was formed to defend the civilians, so we will protect the civilians in the future too. We will work hard, and we will learn, and we will fight.”

Original Post: New Naratif

Announcements

28 February 2025

Asian NGO Network on National Human Rights Institutions , CSO Working Group on Independent National Human Rights Institution (Burma/Myanmar)

Open letter: Removal of the membership of the dis-accredited Myanmar National Human Rights Commission from the Southeast Asia National Human Rights Institution Forum

Progressive Voice is a participatory rights-based policy research and advocacy organization rooted in civil society, that maintains strong networks and relationships with grassroots organizations and community-based organizations throughout Myanmar. It acts as a bridge to the international community and international policymakers by amplifying voices from the ground, and advocating for a rights-based policy narrative.