All parties must ensure unimpeded access to healthcare in Myanmar

- Nearly four months after the military seized power in Myanmar, people are struggling to access healthcare.

- Hospitals are closed or occupied by the military and many facilities are severely understaffed, while COVID-19 remains a threat.

- The economic fallout of the military takeover has also resulted in reduced or uncertain access to services, including healthcare and clean water.

- MSF urges the military government to ensure people have unhindered access to healthcare, and to allow health workers to provide care without fear or intimidation.

Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) calls on Myanmar’s de facto military government, and other groups, to take all steps to ensure people have safe and unhindered access to healthcare, regardless of where they seek it. Equally, medical staff must be able to provide lifesaving care without attacks, detention or intimidation.

As Myanmar approaches four months of military rule, public health services remain severely disrupted. Many public hospitals and clinics are closed or occupied by the military, and those that are open have limited services available while medical staff are on strike. MSF has few options for referring people for specialised treatment. These challenges leave many people struggling to access healthcare.

If a wave of new COVID-19 infections grips Myanmar, it will be a public health disaster given the country’s capacity to test, treat and vaccinate is a fraction of what it was before the military seized power.

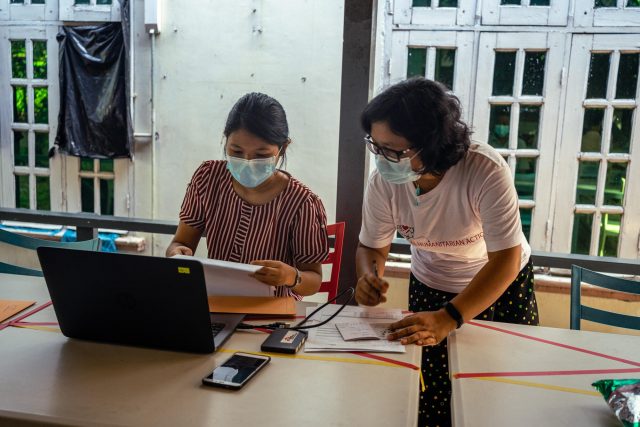

MSF staff members consulting patients at offices in Yangon. Myanmar, April 2021. MSF/BEN SMALL

Insecurity restricts access to healthcare

Patients typically must choose between seeking treatment at a private facility they may not be able to afford, or at a military-controlled hospital where their safety could be at risk, particularly if they have been involved in protests or the civil disobedience movement.

Non-government organisation clinics do exist in some locations, but they are unable to cover all needs and have had their activities restricted by the military authorities. An MSF-supported clinic was told by security forces it could not treat protesters. The security forces visited the facility, ordered the emergency beds removed and insisted all injured people be taken to the military or military-controlled hospitals. Police also arrested one of its volunteers for being involved in protests and demanded names and addresses of others working there. The facility was forced to temporarily close and is now barely functioning, operated by a skeleton staff.

Patients in Myanmar are forced to travel farther to get care at a time when risks are much greater. Security forces at checkpoints scrutinise those moving around, search their belongings, intimidate them and contribute to a climate of fear. For patients with conditions requiring regular and long-term care, such as HIV, tuberculosis and hepatitis C, the ongoing insecurity and delays in accessing medicines could be life-threatening.

“What patients are worried about now is if they can access the clinic to get medication,” an MSF doctor in Kachin state said. “If the security forces at the checkpoints don’t let the patients pass, what can the medical personnel do for their patients?”

Attacks on healthcare workers

Doctors and nurses continue to be targets of violence. Staff working in medical facilities MSF has provided support to have shared reports of medical staff being arrested and detained.

There have been 179 attacks on health staff and facilities since the start of the military takeover, and 13 people have killed in these attacks, according to the World Health Organizations’s Surveillance System of Attacks on Healthcare.

Media reports have shown emergency medical workers and first responders on the frontlines of peaceful protests being shot at with live rounds, while trying to help the wounded. Our partners have also witnessed raids on organisations providing first aid to injured protesters, and their supplies destroyed.

Economic fallout threatens humanitarian response

As the public health system in Myanmar deteriorates, its economy is also collapsing. Cash is increasingly difficult to obtain, with people facing huge queues at sporadically filled ATMs. The kyat – the local currency – has fallen 17 per cent against the US dollar, pushing up the cost of imports and goods like cooking oil, rice and fuel.

Humanitarian agencies are not immune to this liquidity crisis. Facing shortfalls in cash and increased costs can prevent organisations, including MSF, from buying supplies and medications, paying staff salaries and moving goods around.

We are already seeing the impact of this in our HIV programme in Kachin state. Before 1 February, we had been gradually shifting our HIV patient cohort to the government’s National AIDS Programme. However, these clinics are no longer open, and MSF has seen nearly 2,000 patients return to our facilities for consultations and drug refills, and over 200 new HIV-positive patients register.

In Rakhine state, water and sanitation has long been a problem in camps for the Rohingya, where people rely on humanitarian aid for access to clean water. Now that many organisations are scaling back their activities as they struggle to access cash and get supplies into the camps, we are seeing a spike in people seeking treatment for acute watery diarrhoea.

Reignited conflict exacerbates humanitarian crisis

An estimated 60,000 people in Myanmar have been displaced within the country and 10,000 more in neighbouring nations since the 1 February seizure of power, according to data from UNHCR. This is largely due to a resurgence of conflict in Myanmar’s borderlands, particularly in Chin, Kachin and Kayin states – predominantly between the military and ethnic armed groups, but also increasingly including pro-democracy people’s defence forces. Airstrikes and shelling are forcing people to flee their homes and have caused an unknown number of civilian casualties.

MSF had to withdraw staff from one town in Kachin state due to fighting, temporarily interrupting our services, while the sound of shelling and gunshots are commonplace in several locations. This impacts our activities and staff wellbeing, and raises significant concerns for people’s ability to travel to seek healthcare. Medical staff and humanitarian organisations must be protected from violence and given unhindered access to conflict areas to ensure those at risk can access lifesaving care.

MSF fears for the people of Myanmar in this worsening crisis. All obstacles preventing sick and wounded people from seeking healthcare, including the violence, detainment and intimidation of health workers, must be dismantled.

Announcements

21 May 2025

Open letter: Malaysia must lead ASEAN with principle, not hypocrisy, to address the Myanmar crisis

Progressive Voice is a participatory rights-based policy research and advocacy organization rooted in civil society, that maintains strong networks and relationships with grassroots organizations and community-based organizations throughout Myanmar. It acts as a bridge to the international community and international policymakers by amplifying voices from the ground, and advocating for a rights-based policy narrative.