Where Poets Are Being Killed and Jailed After a Military Coup

25 May 2021

More than 30 poets have been imprisoned since the military seized power in Myanmar, a country where politics and poetry are intimately connected.

By Hannah Beech

May 25, 2021 Updated 11:20 a.m. ET

After the first and second poets were killed, the third poet wrote a poem.

They shoot at heads

But they do not know

That revolution lives in the heart.

After the third poet was killed, the fourth poet wrote a poem.

Don’t let your blood run cold

Pool your blood for this fight.

After the fourth poet was killed, his body consumed by fire on May 14, there was no verse. At least for a moment.

Poetry remains alive in Myanmar, where unconventional weapons are being used to fight a military that has killed more than 800 people since it staged a coup on Feb. 1 and ousted an elected government. For some democracy activists, their politics cannot be separated from their poetry.

Sensing the power of carefully chosen words, the generals have imprisoned more than 30 poets since the putsch, according to the National Poets’ Union. At least four have been killed, all from the township of Monywa, which is nestled in the hot plains of central Myanmar and has emerged as a center of fierce resistance to the coup.

“Anti-authoritarian sentiments have always been in the flesh and blood of poets,” said U Yee Mon, a poet who also serves as the defense minister for a shadow democratic government that is challenging Myanmar’s junta from jungle redoubts. “The people with weapons are afraid of pen-wielding hands.”

A Buddhist monastery during protests in Yangon, Myanmar, in February. The New York Times

The resistance to Myanmar’s military, which has dominated the country since its independence from Britain, has inspired people from all walks of life. Students and beauty queens have protested, as have doctors and engineers. Poets have joined the protests, too, their rhyming couplets providing battle cries for the movement.

The first poets to be killed by security forces in the aftermath of the coup were Ko Chan Thar Swe and Ma Myint Myint Zin. One was shot in the head and the other in the chest during a mass protest in Monywa in early March.

Mr. Chan Thar Swe had left the Buddhist monkhood to write poetry more than a dozen years ago, a move that shocked his family, which had basked in the prestige of having a cleric among them, said his sister Ma Khin Sandar Win. His poems, written under the pen name K Za Win, were full of a vigor that belied his monastic background.

His political activism, on behalf of land, education and environmental causes, landed him in prison in 2015. Dozens of poets shared the same fate. Mr. Chan Thar Swe composed in his cell, the poems crowding his head. By then, prisoners were allowed books, but not pens. So he memorized his verse. The rigor helped clarify his poetry, which is free of excess. Five days after the coup, he wrote “Revolution.”

Dark nights

They linger too long.

The poem ends on a hopeful note.

It will be dawn

For it is the duty of those who dare

To conquer the dark and usher in the light.

Ko Chan Thar Swe, who had left the Buddhist monkhood to write poetry, was killed in March

On March 4, his sister received a police summons to the Monywa mortuary. She identified her brother’s body, Ms. Khin Sandar Win said. A bullet hole punctured his left temple. A long slash ran down his torso.

The family wondered whether the gash signaled that his internal organs had been removed, a desecration increasingly found among those killed by the military in Myanmar. But Mr. Chan Thar Swe was cremated before his relatives could find out more.

His mother now spends her days looking at photographs of him, her oldest child, on Facebook. Along with his ashes, it is all she has of him.

“My brother did not support us financially because he was a poet, but he protected us whenever we needed,” Ms. Khin Sandar Win said.

At Mr. Chan Thar Swe’s funeral, another poet, Ko Khet Thi, recited a poem he had written for those killed by the security forces, many with a single bullet to the head and some when they were not even protesting.

They began to burn the poets

When the smoke of burned books could

No longer choke the lungs heavy with dissent.

Weeks after the funeral, Mr. Khet Thi, a onetime engineer, was hauled into detention and later turned up dead, according to his family. His corpse also had an unexplained incision down his torso, the family said.

“I am also afraid that I will get arrested and killed, but I will keep fighting,” said Ko Kyi Zaw Aye, yet another poet from Monywa who was close to both men.

A protest in Yangon in February. The resistance to Myanmar’s military has inspired people from all walks of life. The New York Times

Political poetry in Myanmar dates to the days when Burmese kingdoms employed troubadours to galvanize soldiers before battle. When the population chafed at the oppression of the British Empire, poets led the charge in the independence movement.

The lyricism of the Burmese language, with its rhyming syllables and vivid imagery built into everyday phrases, helped to elevate poetry as a potent national art form. It also helped camouflage true meanings, an important tool when dealing with censorious colonial administrators or army generals.

In 2015, when the National League for Democracy challenged the military’s proxy party in the first free and fair parliamentary elections in a generation, the party fielded nearly a dozen poets, all of whom won. Mr. Yee Mon, the shadow government’s defense minister, was one such victor.

He defeated the former defense minister in a district where many soldiers and police officers voted. A rapper and a painter prevailed in other races, part of the National League for Democracy’s overwhelming victory, which was repeated last November with an even more resounding performance.

Last week, a junta-appointed official said the party was full of “traitors” and might be dissolved. The party’s leader, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, appeared in court on Monday, the first time she had been seen in person since most of the country’s elected leadership was jailed in the military coup.

When some poets spent time behind bars, they sometimes used rocks to carve the curved Burmese script of their poems onto cell walls. Mr. Yee Mon relied on a bit of metal against plastic to record his words.

Listening to Rohingya poets at “Poetry for Humanity,” an event in Yangon in late January, less than a week before the coup. Sai Aung Main/Agence France-Presse — Getty Image

Even after the democratic opposition began to share power with the military in 2015, poets still were dispatched to prison. One, Ko Maung Saungkha, wrote a poem about having tattooed his penis with a reference to a former president handpicked by the army. He was imprisoned for six months in 2016, despite having made clear that such a tattoo did not, in fact, exist.

The intertwining of dissent and poetry has continued.

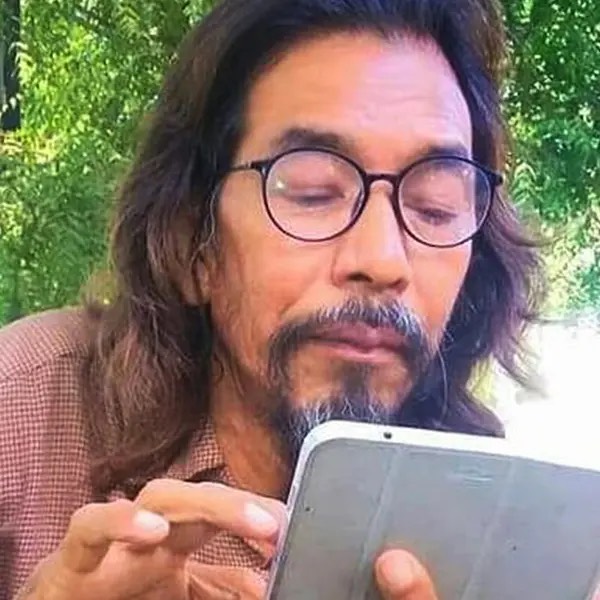

U Sein Win was a National League for Democracy stalwart in Monywa. He painted and carved wood. He wrote poetry and plays. When he spoke, his hands danced with his words. His long hair framed his face.

On the morning of May 14, an assailant threw a bucket of gasoline on Mr. Sein Win, 60, and lit a match, according to his daughter, Ma Thin Thin Nwe. His facial features melted away. He died that night. Since the coup, more than a dozen democratic politicians, activists and ordinary people have died from such unexplained assaults.

U Sein Win was a National League for Democracy stalwart in Monywa. He painted and carved wood and wrote poetry and plays

At Mr. Chan Thar Swe’s funeral, weeks before he was killed himself, Mr. Khet Thi prophesied the destructive power of fire and the rebirth that follows.

They started to burn the poets

But ash makes for more fertile soil.

Original Post:The New York Times

Announcements

28 February 2025

Asian NGO Network on National Human Rights Institutions , CSO Working Group on Independent National Human Rights Institution (Burma/Myanmar)

Open letter: Removal of the membership of the dis-accredited Myanmar National Human Rights Commission from the Southeast Asia National Human Rights Institution Forum

Progressive Voice is a participatory rights-based policy research and advocacy organization rooted in civil society, that maintains strong networks and relationships with grassroots organizations and community-based organizations throughout Myanmar. It acts as a bridge to the international community and international policymakers by amplifying voices from the ground, and advocating for a rights-based policy narrative.