Bangladesh: Remove Fencing, Support Fire-Affected Refugees

05 May 2021

Barbed-wire fencing contributed to loss of life, injuries in deadly camp fires

(BANGKOK, May 5, 2021)—The Government of Bangladesh should remove barbed-wire fencing confining Rohingya refugees to camps and support those affected by suspicious fires that destroyed buildings and shelters and killed at least 14 refugees in Cox’s Bazar District since January 2021, said Fortify Rights today.

“Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina should order the immediate removal of barbed-wire fencing surrounding the Rohingya camps,” said Ismail Wolff, Regional Director at Fortify Rights. “The fences are a deadly experiment that infringe on basic freedoms and have now contributed to injury and death.”

In April 2021, Fortify Rights interviewed 13 refugee eyewitnesses and other Rohingya in Cox’s Bazar District who said that barbed-wire fencing enclosing the camps hampered efforts to escape fires and directly contributed to injuries and at least one death during a major blaze in the Kutupalong-Balukhali camp on March 22. Fortify Rights also spoke with five humanitarian aid workers operational in Bangladesh and reviewed and analyzed videos and photographs of the recent fires and aid-agency maps of the fencing.

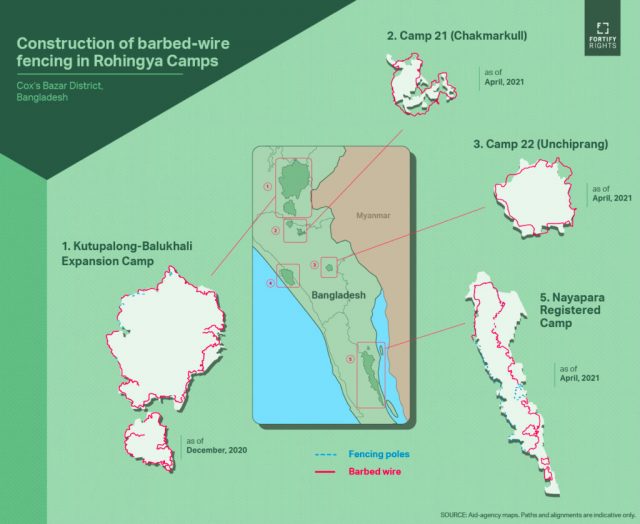

The fencing, which the Bangladesh authorities erected during the past 17 months, is part of a broader system of restrictions on refugees’ freedom of movement. The fencing surrounds the camps and includes limited exit points, confining nearly one million Rohingya refugees who fled persecution and genocide in Myanmar and creating unnecessary protection risks.

©Fortify Rights, 2021

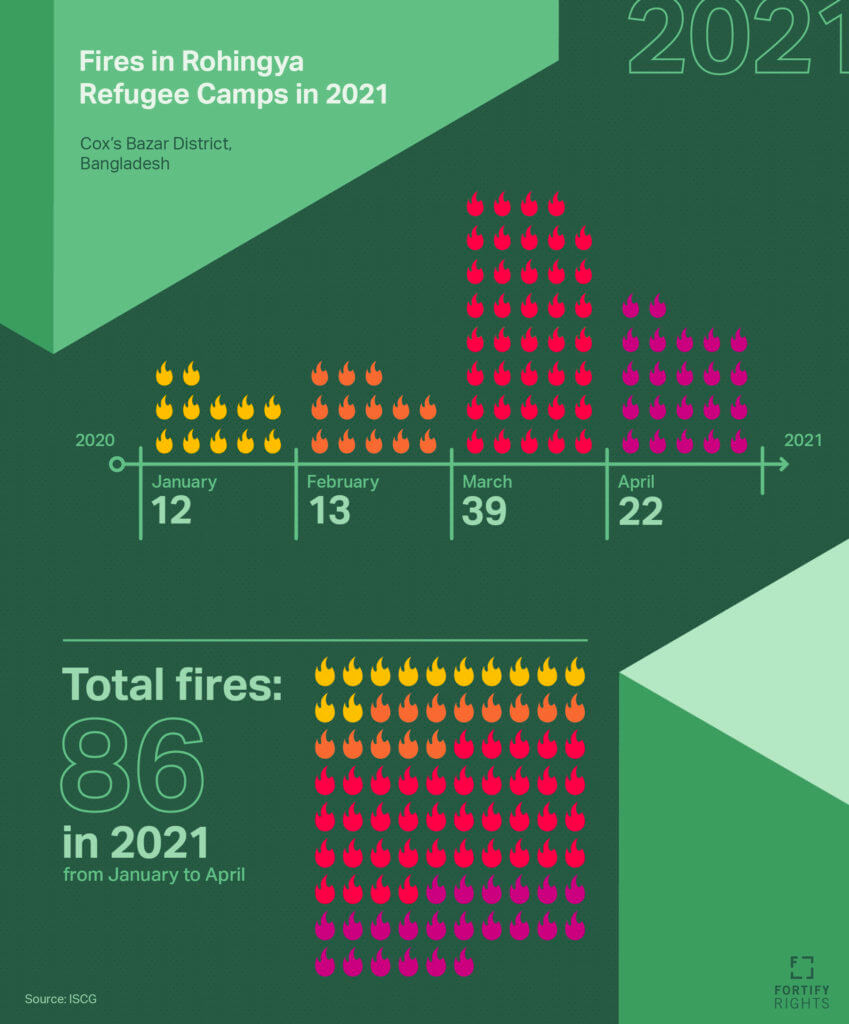

At least 86 fire incidents occurred in at least 25 of the 34 Rohingya refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar District this year, according to data reviewed by Fortify Rights from the Inter-Sector Coordination Group (ISCG)—the central coordinating agency for the international Rohingya refugee response in Bangladesh. The incidents ranged from minor fires that were quickly extinguished to major blazes that left at least 14 dead, hundreds injured, and thousands without shelter, according to the U.N. refugee agency and media reports.

In the most severe incident this year, a massive daytime fire engulfed large sections of the Kutupalong-Balukhali camp on March 22, affecting more than 48,000 people and leaving 10,100 households without shelter according to ISCG. The fire resulted in at least 11 deaths and injured more than 560 people, according to a joint assessment conducted by humanitarian organizations operational in Bangladesh. The fire began in the afternoon and spread rapidly through four sections of the camp.

Some refugees are still rebuilding their homes as monsoon season approaches.

©Fortify Rights, 2021

A Rohingya man, 23, in Balukhali camp described seeing a young man being burned as he attempted to escape the fire on March 22:

He was trying to climb the fence. The barbed wire cut him. It was impossible to jump. He tried to climb the fence . . . Suddenly, the fire caught up to him. This happened as he was trying to escape and jump the fence . . . The fire was so dangerous, and people could not rescue him.

A Rohingya family member later confirmed with Fortify Rights the young man had died in the fire.

“Some were climbing the wire fence to escape,” said a 29-year-old Rohingya refugee who was in the camp during the fire on March 22 and saw at least 15 people injured. “Those who could not escape were burned in the fire.”

A 27-year-old Rohingya woman from Balukhali camp described to Fortify Rights her attempt to flee the March 22 fire with her three-month-old child:

I saw black smoke in the sky . . . [and then] the fire became very close. I started to go back to Boli Bazar market and saw that it was also on fire. When the fire became dangerously close, we started fleeing towards the fencing. We tried to get over [the fence]. We were running here and there inside the fencing. We ran along the border of the fence but couldn’t jump over it . . . It was such a horrible day. I thought my baby and I were going to die . . . We have lost everything. My shelter and belongings are all burned.

A Rohingya on the other side of the fence cut through the fence with bolt cutters, rescuing the woman and her child. She described how others tried to get through the fence:

Some men used their hands to break the fence, injuring their hands on the barbed wire. People were cut by the barbed wire trying to flee. They got stabbed in the legs, arms, head, and back. Some were bleeding . . . The fence should be taken down.

On April 12, another fire occurred in Balukhali camp, damaging several buildings and shelters. A Rohingya refugee man, 26, told Fortify Rights he witnessed Bangladesh police beat a Rohingya man trying to extinguish the flames:

I saw it myself. The police beat him with the end of their guns and a stick. The police hit him more than five times. He was trying to put out the fire . . . There were three police hitting him. The rest of the police tried to push the other people back to prevent them from putting out the fire.

On March 24, Bangladesh Home Affairs Minister Asaduzzaman Khan Kamal visited the fire-affected areas of Balukhali camp and defended the fencing, telling journalists the fence did not “create any hindrance against the rescue operation” and claimed that the fence helped create “law and order in the camps.”

During his visit, Asaduzzaman Khan Kamal announced the launch of an investigation into the cause of the March 22 fire, saying, “We formed two investigation committees to identify the causes behind the fire; they are working on it.” He also told journalists the Bangladesh government had not ruled out that a “subversive plan” could be the cause of the fire.

The Bangladesh Refugee Relief and Repatriation Commissioner Shah Rezwan Hayat confirmed to the media their involvement in leading an “eight-member high power inquiry committee” to investigate the March 22 fire, saying on March 25: “We are on the field, trying to determine the source or cause of the fire. But we are not yet sure about the source of fire.”

A four-member committee led by the Bangladesh Fire Service and Civil Defence is also reportedly tasked with determining the source of the fire and estimating the losses.

“The government should evaluate fire safety within the camps, including how the fencing contributed to casualties,” said Ismail Wolff. “The results of the investigation should be made public and communicated to the refugee population.”

Several refugees told Fortify Rights they suspect arson as a cause of the recent upsurge in fires in the camps.

Last year, ISCG recorded 81 fires in the camps for the entire year of 2020, compared with 86 fires in the first four months of 2021.

There are upwards of one million Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh. The government has intermittently erected fencing around refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar District since September 2019 when it first announced plans to construct watchtowers, install video surveillance, and fence off more than 30 Rohingya refugee camps. The Bangladesh government says the fencing is in response to security concerns and to control the movement of Rohingya refugees in and out of the camps.

In a 2020 report by Fortify Rights, 65 percent of Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh cited restrictions on freedom of movement—including problems moving between places, checkpoints, and extortion—as a “chronic stressor.”

The Bangladesh government constructed the barbed-wire fencing without engaging in meaningful consultations with refugees, host communities, or aid agencies to assess the proposal and consider alternatives. The fencing contributes to distress and trauma among Rohingya refugees who fled genocidal arson attacks and similar freedom of movement restrictions in Myanmar, Fortify Rights said.

Bangladesh is a state party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which applies “without discrimination” to refugees and protects the right to freedom of movement. Any restriction on the right to freedom of movement must be provided by law, strictly necessary, and proportionate for a legitimate purpose under international law. The fencing and confinement of upwards of one million refugees in Bangladesh fails to meet these conditions and, therefore, violates the right to freedom of movement.

“Confining genocide survivors to fenced-in camps not only creates unnecessary risks but also exacerbates fear within the camp,” said Ismail Wolff. “The government should remove these fences without delay.”

Announcements

28 February 2025

Asian NGO Network on National Human Rights Institutions , CSO Working Group on Independent National Human Rights Institution (Burma/Myanmar)

Open letter: Removal of the membership of the dis-accredited Myanmar National Human Rights Commission from the Southeast Asia National Human Rights Institution Forum

Progressive Voice is a participatory rights-based policy research and advocacy organization rooted in civil society, that maintains strong networks and relationships with grassroots organizations and community-based organizations throughout Myanmar. It acts as a bridge to the international community and international policymakers by amplifying voices from the ground, and advocating for a rights-based policy narrative.