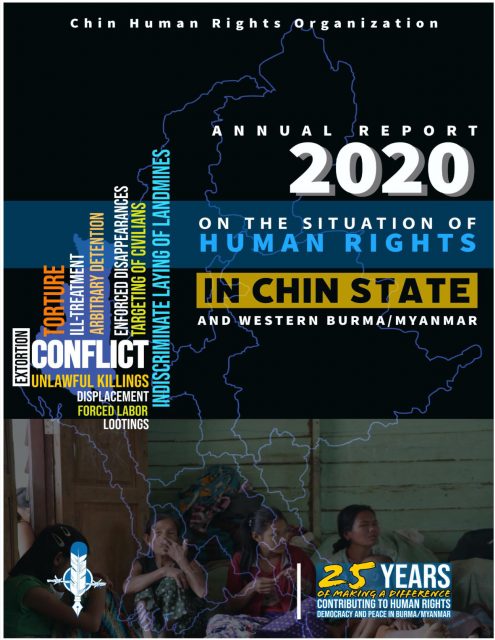

Annual Report 2020: On the Situation of Human Rights in Chin State and Western Burma/Myanmar

18 December 2020

For the Chin communities living in Paletwa Township and Northern Rakhine State, 2020 has seen the largest escalation of conflict and resulting civilian casualty since the conflict began in 2015. Within the past 11 months, patterns of human rights violations (HRVs) have been linked to several different factors.

After the World Health Organisation (WHO) officially declared COVID-19 a global pandemic, the UN Secretary-General, Antonio Gutierrez, appealed for a global ceasefire to address the crisis. Despite calls from United Nations bodies, diplomatic missions, civil society, and Ethnic Armed Organisations (EAOs) to implement a ceasefire, the military government increased hostilities and operations in Paletwa and Northern Rakhine. During February, March and April, Paletwa Township endured the worst state atrocities committed at anypoint since 2015. Violations of international humanitarian law (IHL) included a spate of airstrikes on villages bordering Paletwa Township and Rakhine Stateby the Tatmadaw resulting in 36 deaths and 27 injuries to the local population. In April, Yanghee Lee, the outgoing U.N. Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, said in a statement that the country’s armed forces were escalating assaults, targeting the civilian population while the world was“occupied with the COVID-19 pandemic”. The coordinated and sustained attacks on the civilian population, according to the United Nations High Commission for Human Rights (OHCHR), were designated as possible war crimes and crimes against humanity in calling for the Tatmadaw and AA to protect civilians and for accountability into the atrocities.

Increases Of Violations of IHL law are also linked to the designation of the AA as a terrorist outfit in March. On 23 March the Myanmar Government designated the armed group as a terrorist group under the 2014 Counter-Terrorism Law. President Win Myint also declared that the AA, its political wing, the United League of Arakan (ULA), and affiliated groups and individuals “have constituted a danger to law and order, peace and stability of the country and public peace” and are unlawful under Section 15(2) of the Unlawful Associations Act. The AA initiates guerilla tactics, often plain-clothed and without fixed positions. This approach to conflict, coupled with brazen attacks on senior political figures, abductions of elected members of parliament and an active public relations agenda which includes threats to uncover the locations of mass graves of Rohingya carried out during the 2017 clearance operations led to the designation.

The unilateral ceasefire that was eventually announced by the Military Government in May to fight COVID-19, did not extend to the people in the conflict-affected areas of Chin and Rakhine State due to the designation of the AA as a terrorist group. Under the terror legislation, the government also censored ethnic media outlets and arrested journalists retroactively for interviewing members of the AA. The censorship of ethnic media outlets, coupled with the ongoing internet blackout, still enforced since June 2019 meant that the timely documentation of HRVs became even more challenging. Humanitarian groups also complained of how the ongoing internet blackout continued to hamper the coordination of aid, collection of accurate information, and monitoring of abuses and in some villages, people were completely unaware of the COVID-19 outbreak.

The space that local communities are forced to exist within, between the AA and the Tatmadaw, has continued to shrink in 2020. CHRO has documented instances of torture carried out by both armed groups, where civilians have been targeted due to suspicion of cooperating with the other party to the conflict. The AA continues to use enforced disappearance, arbitrary arrest and detention and torture and other forms of ill-treatment or punishment to instil fear into communities. Due to sporadic but intense fighting, community members have also regularly been caught in cross-fire, usually while travelling on trade routes connecting main towns. The indiscriminate laying of landmines has continued to create a significant risk of injury or death in accessing farms, water facilities and in undertaking traditional forms of livelihoods such as foraging in forested areas.

During the first half of 2020, as trade routes and access to main towns were restricted, inflation on food and non-food items took place. In Paletwa Town, as IDP numbers increased and rice stocks dwindled, the community were forced to survive on the stems of banana trees and strict rationing of rice. The crisis was exacerbated by the looting of WFP-contracted trucks en-route to Paletwa Town by the AA, and the widespread looting of livestock by Tatmadaw forces in villages close to Paletwa Town, previously deserted. In the North of Paletwa Township, communities from multiple villages faced arbitrary taxation of rice stocks and forced labour by the AA.

In 2020 the conflict in Paletwa Halted the democratic process in Chin State and severely disrupted the workings of local government and civil service. In November, Myanmar’s Union Election Commission announced that voting would not take place in 94 of the 102 village tracts in Paletwa Township. Due to security concerns associated with the conflict more than 200 teachers in Paletwa applied for transfers to other locations. In February, the escalating conflict in Paletwa forced school closures before exams were scheduled to take place. Out of 391 schools in the township, 191 were closed before COVID-19 closed all schools in the country and a further 100 were operating without full-time teaching posts. In January, more than 210 government employees in Chin state resigned in fear of their safety after it was alleged that the AA had been issuing threats. In July, 500 people, many of whom were health workers and education department staff were continually shot at by a Tatmadaw outpost along the Kaladan River, as they attempted to return home from Paletwa Town after an annual meeting was held.

The government responses to the COVID-19 have also enforced a number of systemic inequalities in Chin State and to religious minorities more generally. Laws which govern lockdown measures, such as the gathering of over 5 people, night-time curfews and lockdowns have disproportionality criminalized ethnic minorities. Cases include stiffer legislation which resulted in jail time for breaking lockdown measures which have both been enforced disproportionality and in a seemingly ad-hoc fashion. Furthermore, in Chin State, the township-level COVID-19 Response Committees lack ethnic/local representation which has led to discriminatory decision making. In October, a family was forced to bury the body of a dead girl at the side of a road after a funeral arrangement was banned from entering Thantlang Town.

Announcements

21 May 2025

Open letter: Malaysia must lead ASEAN with principle, not hypocrisy, to address the Myanmar crisis

Progressive Voice is a participatory rights-based policy research and advocacy organization rooted in civil society, that maintains strong networks and relationships with grassroots organizations and community-based organizations throughout Myanmar. It acts as a bridge to the international community and international policymakers by amplifying voices from the ground, and advocating for a rights-based policy narrative.