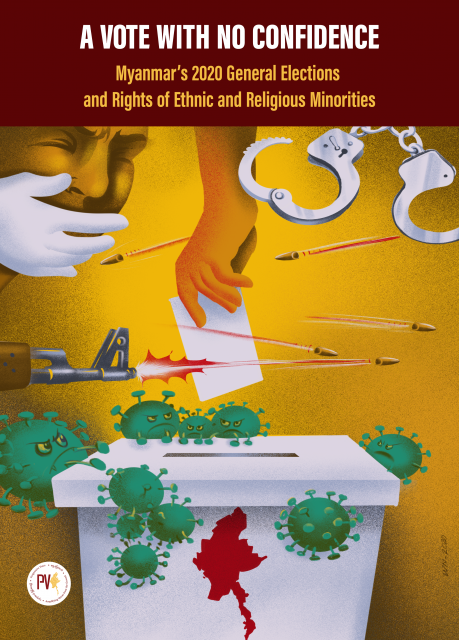

A Vote with No Confidence: Myanmar’s 2020 General Elections and Rights of Ethnic and Religious Minorities

26 October 2020

Introduction

In less than two weeks, on 8 November 2020, the Myanmar public will take to the polls and cast their vote in a national election. The 2020 general elections are the second to be held since reforms under Myanmar’s military-drafted 2008 Constitution were implemented in 2011, after an election in 2010 brought the Constitution into effect. Although not touted with the same ‘historic’ or ‘landmark’ status as the 2015 general elections, this year’s electoral process remains an important event given the troubled context of Myanmar’s post-independence history, the majority of which was served under the repressive rule of consecutive military regimes dominated by the country’s Bamar Buddhist majority.

Fanfare aside, the 2015 general elections, which saw Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and the National League for Democracy (NLD) win a landslide 79.4% of the vote, were largely regarded by international and domestic observers as peaceful and free from irregularities. However, arbitrary and discriminatory decisions concerning the implementation of Myanmar’s flawed citizenship legal framework and ongoing armed conflict and insecurity had in fact left hundreds of thousands of people from ethnic and religious minorities disenfranchised, while the absence of an independent election commission with sufficient capacity, cancelled voting in ethnic areas, inconsistencies with voting lists, soldiers voting within barracks, and other issues all raised serious questions over the credibility of the vote.

Five years on, and the NLD government has failed to deliver on structural reform of key institutions such as the military and judiciary; repealing repressive laws that curtail freedom of expression, association and assembly; resolving root causes of decades-long armed conflict; and ending the discrimination and violent persecution of Myanmar’s ethnic and religious minorities. The role of civil society continues to be undermined, federal rights of ethnic nationalities are not being recognized, hate speech, intolerance and incitement to violence continue to circulate at dangerous levels, and the country is facing charges of genocide at the highest court in the world. The democratic space in Myanmar remains stifled and confined within the provisions of the military-drafted 2008 Constitution, under which 25% of seats in parliament are reserved for the military – a fundamental violation of democratic norms. Under these circumstances, the 2020 general elections cannot be considered fully democratic.

International human rights standards for democratic elections derive from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR):

Everyone has the right to take part in the government of their country, directly or through freely chosen representatives; the will of the people will be the basis of the authority of government; this shall be expressed in periodic and genuine elections which will be by universal and equal suffrage and held by secret vote or by equivalent.

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) elaborates:

Every citizen, without discrimination, has the right to vote and to be elected at genuine periodic elections, by universal and equal suffrage and held by secret ballot, guaranteeing the free expression of the will of the electors.

Myanmar is one of very few countries in the world not to have ratified the ICCPR, which is a central pillar of the international human rights framework. Despite persistent efforts and advocacy by Myanmar civil society and members of parliament calling on the government to sign the ICCPR, military members of parliament and their allies have consistently voted to obstruct the motion.

The conditions needed for individuals to fully exercise their right to vote in line with the UDHR and ICCPR also requires realization of the rights to freedom of expression, association and assembly, freedom of movement and information, and freedom from coercion. There should be no discrimination with respect to the right to stand for election, such as on the basis of education, residence or descent, or by reason of political affiliation. No person should suffer discrimination or disadvantage of any kind because of their candidacy. Finally, an independent electoral authority should be established to supervise the electoral process and to ensure that it is conducted fairly and impartially.

There are many context specific factors in Myanmar that are severely undermining these standards. Institutionalized discrimination coupled with vigorous advocacy by extreme Bamar Buddhist nationalist movements are denying vast numbers of Myanmar’s ethnic and religious minorities their right to vote or stand for election. Ethnic communities plagued by armed conflict and displacement are also at risk of losing their right to vote, while ethnic political parties and candidates are being marginalized. These issues are being compounded by the second wave of COVID-19, tight restrictions on freedom of expression, limitations on access to information and the role of the Myanmar military in subverting votes, all of which are disproportionately impacting on the political rights of ethnic and religious minorities and call into question the credibility of the 2020 general elections. Despite these serious shortcomings amounting to violations of political rights, there has been no response from the Myanmar National Human Rights Commission (MNHRC), which speaks to the inadequacy of the MNHRC as an independent and impartial body entrusted with promoting and safeguarding the fundamental rights of citizens in accordance with the Principles relating to the Status of National Human Rights Institutions (Paris Principles).

The purpose of this briefing paper, which is drawn predominantly from secondary research and interviews, is to provide an overview and background on some of these key issues undermining the integrity of Myanmar’s 2020 general elections. There are many issues of concern to human rights that warrant further analysis and discussion, such as the poor representation of women and LGBTIQ+ political candidates, or candidates with disabilities, for example. However, the focus of this paper is on several overriding, interconnected and egregious challenges to human rights in Myanmar and their subsequent impact on the political rights of ethnic and religious minorities. Those challenges are broadly categorized as relating to nationalism and citizenship; conflict and displacement; COVID-19; freedom of expression; and the Myanmar military. These are followed by a conclusion and recommendations.

Announcements

21 May 2025

Open letter: Malaysia must lead ASEAN with principle, not hypocrisy, to address the Myanmar crisis

Progressive Voice is a participatory rights-based policy research and advocacy organization rooted in civil society, that maintains strong networks and relationships with grassroots organizations and community-based organizations throughout Myanmar. It acts as a bridge to the international community and international policymakers by amplifying voices from the ground, and advocating for a rights-based policy narrative.