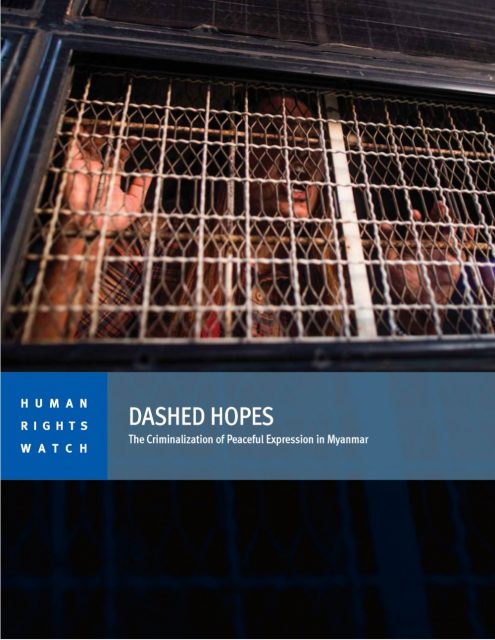

Dashed Hopes: The Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Myanmar

31 January 2019

Summary

The National League for Democracy (NLD) took office in March 2016 as the first democratically elected, civilian-led government in Myanmar since 1962, generating tremendous optimism that the country would see a significant shift toward openness. Parliament itself included 100 new members who were former political prisoners, and there was reason to hope the government would implement far-reaching reforms to laws and policies that had long restricted freedom of expression and assembly in the country.

That optimism has proved unfounded. With limited exceptions, parliament has thus far failed to make substantive changes to most of the laws used against speech and assembly. Instead, it has often done the opposite, strengthening some abusive laws and enacting at least one law imposing new restrictions on speech. As one member of the Protection Committee for Myanmar Journalists put it, “If the government doesn’t like what you say, they can charge you with any law. If there is no law, they can make a new one and charge you with that.”

While discussion of a wide range of topics now flourishes in both the media and online, those speaking critically of the government, government officials, the military, or events in Rakhine State frequently find themselves subject to arrest and prosecution. “When we talk in the media [about controversial topics], anything can happen, but we have to keep speaking,” said Thinzar Shunlei Yi, advocacy director of Action Committee for Democracy Development. “We say it is like the lucky draw. You don’t know when it will happen.”

The decline in freedom of the press under the new government has been particularly striking. As Zayar Hlaing, editor of the investigative magazine Mawkun and executive member of the Myanmar Journalist Network, said, “Before the 2015 election, the NLD said it would protect press and promote independent media. After two years, press freedom is worse day by day.”

This report—based largely on interviews in Myanmar and analysis of legal and policy changes since 2016—assesses the NLD government’s record on freedom of expression and assembly in its more than two years in power. It updates Human Rights Watch’s prior report, “They Can Arrest You at Any Time”: The Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Burma, issued in June 2016, focusing on the laws most commonly used to suppress speech. We conclude that freedom of expression in Myanmar is deteriorating, directly affecting a wide range of people, from Facebook users critical of officials to students performing a satirical anti-war play. Domestic journalists are particularly at risk.

* * *

In the past two and a half years, an increasing number of journalists have been arbitrarily arrested, detained, imprisoned, and physically attacked. They have been denied access to both conflict areas and information about government policies and programs. Unsurprisingly in this environment, a 2018 survey of journalists by Free Expression Myanmar found that “the government, including the military, is the greatest threat to media freedom in Myanmar, both through its continued use of old oppressive laws which it has no real plans to amend, and its adoption of new oppressive laws.”

The authorities have arrested journalists under a range of laws including the Telecommunications Law, the Unlawful Associations Act, and the Official Secrets Act. According to numbers compiled by Athan, a local organization working to improve freedom of expression in Myanmar, at least 43 journalists had been arrested under the NLD-led government as of September 30, 2018. “It has a chilling effect on journalists and those who work with them,” said Zayar Hlaing.

Certain topics are viewed as particularly risky to cover. According to journalist Aung Naing Soe, “Criticism of ‘the Lady’ [Aung San Suu Kyi] or the NLD can cause problems. The most dangerous issue is the Rohingya.” A leading member of the Protection Committee for Myanmar Journalists said the Rohingya and the military are “untouchable” issues: “If a journalist wants to report on human rights abuses by the military, it is a big issue. In the past we had these issues, but there are more now. It is very damaging for us.”

The result has been a climate of fear among local journalists. Said one: “We are more afraid than international journalists because we are more vulnerable—we are living in the country. For us as local journalists, there is no guarantee of our work security or our safety.”

As journalist Lawi Weng put it, “I often say that journalists in Burma don’t have a parent or father to look after them. We are orphans. We don’t know who will help us. We are still working despite the risks, but there is no one who can protect us.”

Journalists who tackle difficult topics also face threats from ultranationalists and militant supporters of the government or army, with little support from the authorities against such threats. The Myanmar Journalist Network was evicted from their office by their landlord after a large group of ultranationalists gathered at the office to protest a planned press conference. Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Esther Htusan of the Associated Press left the country after serious threats by government supporters who were displeased with her reporting on Aung San Suu Kyi.

One result for many journalists and media outlets is self-censorship. After the government arrested Irrawaddy reporter Lawi Weng under the Unlawful Associations Act for his reporting, the paper no longer let him report from the military front lines. “They wouldn’t send any reporters to the front line,” he said. “So we no longer know what is going on on the ground.”

It is not only journalists who are facing prosecution for peaceful speech. Arrests and prosecutions under section 66(d) of the Telecommunications Law have soared. The authorities have prosecuted individuals for criticizing the military, for live-streaming a satirical anti-war play, and for social media posts that other private citizens deemed insulting. “Among friends we even joke, ‘If you say that, 66(d) is waiting for you,’” said Thinzar Shunlei Yi. “It makes us censor ourselves. It creates fear in the youth community. We are still living in fear.”

The government has also continued to prosecute peaceful speech under other abusive laws identified in our 2016 report, including criminal defamation and section 505(b) of the Penal Code, which criminalizes speech that “is likely to cause fear or alarm in the public.” The authorities have used section 505(b) to prosecute a former child soldier for talking about his experiences, a music group for a song calling for changes in the constitution, and an activist who alleged human rights abuses by the military. The newly enacted Law Protecting Privacy and Security of Citizens has also been used to prosecute speech.

Individuals are still being prosecuted for organizing or participating in peaceful assemblies, with those protesting against the military most often subject to arrest. In May 2018, police arrested at least 45 people involved in a series of protests against the armed conflict in Kachin State, with most facing charges under the Peaceful Assembly and Peaceful Procession Law.

Human Rights Watch reiterates its call for the Myanmar government to cease using criminal laws against peaceful speech and assembly, and to bring its laws, policies, and practices in line with international human rights law and standards for the protection of freedom of expression and assembly. Friendly governments should privately and publicly weigh in with their concerns on these important issues.

View this original post HERE.

Download full report in English HERE.

Download the summary and recommendations in Burmese HERE.

Announcements

28 February 2025

Asian NGO Network on National Human Rights Institutions , CSO Working Group on Independent National Human Rights Institution (Burma/Myanmar)

Open letter: Removal of the membership of the dis-accredited Myanmar National Human Rights Commission from the Southeast Asia National Human Rights Institution Forum

Progressive Voice is a participatory rights-based policy research and advocacy organization rooted in civil society, that maintains strong networks and relationships with grassroots organizations and community-based organizations throughout Myanmar. It acts as a bridge to the international community and international policymakers by amplifying voices from the ground, and advocating for a rights-based policy narrative.