“Bangladesh Is Not My Country”: The Plight of Rohingya Refugees from Myanmar

05 August 2018

Summary

In late August and September 2017, Bangladesh welcomed the sudden influx of several hundred thousand Rohingya refugees fleeing ethnic cleansing in Myanmar. This followed an earlier wave of violence in October 2016, which forced over 80,000 Rohingya to flee to Bangladesh. Bangladesh’s respect for the principle of nonrefoulement is especially praiseworthy at a time when many other countries are building walls, pushing asylum seekers back at borders, and deporting people without adequately considering their protection claims. Currently, more than 900,000 Rohingya refugees are in the Cox’s Bazar area in Bangladesh’s southern tip. These consist of nearly 700,000 new arrivals on top of more than 200,000 Rohingya refugees already living in the area, having fled previous waves of persecution and repression in Myanmar. Bangladesh has continued to let in another 11,432 since the beginning of 2018 through the end of June 2018.

While the burdens of dealing with this mass influx have mostly fallen on Bangladesh, responsibility for the crisis lies with Myanmar. The Myanmar military’s large-scale campaign of killings, rape, arson, and other abuses amounting to crimes against humanity caused the humanitarian crisis in Bangladesh. And Myanmar’s failure to take any meaningful actions to address either recent atrocities against the Rohingya or the decades-long discrimination and repression against the population is at the root of delays in refugee repatriation. Bangladesh’s handling of the refugee situation needs to be understood in the context of Myanmar’s responsibility for the crisis.

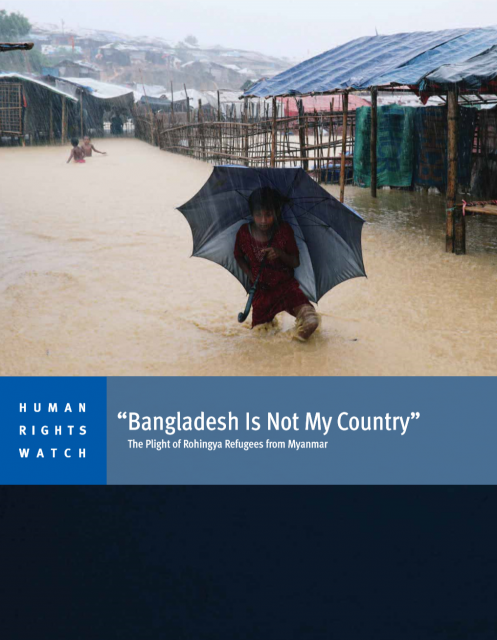

The Kutupalong-Balukhali Expansion Camp near the town of Cox’s Bazar, sometimes referred to as the “mega camp,” is now the world’s largest refugee camp. It was built quickly and haphazardly on a hilly jungle. “Our entire village came together and settled on this spot,” said Amanat Shah, 19, who arrived on September 2, 2017. “At first this was a jungle, but we cleared it. Now there are no trees.” His hut now sits on a densely packed, steep slope with almost no vegetation to keep the clay-sand mix under him from eroding or suddenly sliding away.

The imminent threat for Rohingya refugees is the likelihood that the Cox’s Bazar area will be hit by a cyclone or comparable high winds and storm-surge flooding. Throughout the Human Rights Watch May 2018 visit, refugees were busily shoring up their huts, construction crews were working to build safer locations to accommodate people, and first responders were conducting drills to mitigate disaster. Notwithstanding these efforts, the camps and their residents remain highly vulnerable to catastrophic weather events.

As of June 10, 2018, about 215,000 refugees in the Cox’s Bazar area were at risk of landslides and flooding, with 42,000 at highest risk, but only 19,500 had been relocated from highest risk locations, as of July 4. Evacuation plans in the event of a cyclone or other serious weather event were stymied by the government’s movement restrictions on the refugees and a lack of stable structures in which to evacuate people.

The mega camp is severely overcrowded. The average usable space per person is 10.7 square meters per person, whereas the recommended international standard for refugee camps is 45 square meters per person. Densely packed refugees are at heightened risk of communicable diseases, fires, community tensions, and domestic and sexual violence.

The Rohingyas’ identity as Myanmar nationals motivates their preference for repatriation so long as they are granted citizenship, provided security, and recognized as Rohingya. Both this and their reluctance to criticize their hosts has also made them hesitant to make demands on Bangladesh to improve their current living conditions. “Bangladesh is not my country,” said Kadir Ahmed, age 24. “I want to go back to our land. If the Myanmar government had not killed and tortured us, we would not have left.”

For a variety of reasons, including avoiding having refugees be an issue in upcoming national elections in late 2018, the Bangladeshi central government does not want to acknowledge publicly that the Rohingya refugees will not be repatriating anytime soon—and their stay could be prolonged. The authorities have resisted any efforts by international humanitarian and development agencies or by the refugees themselves to create any structures, infrastructure, or policies that suggest permanency.

As a result, refugee children do not go to school, but rather to “temporary learning centers,” where “facilitators,” not “teachers,” preside over the classrooms. The learning centers are inadequate, only providing about two hours of instruction a day. Most classes are geared toward the pre-primary and early grades of primary school, and there are basically no educational offerings for adolescents or adults. Only one-quarter of school-aged children attend temporary learning centers, which means nearly 400,000 children and youth are not receiving a formal education.

Relocation elsewhere in Bangladesh to a location with fewer environmental risks and adequate standards of services is crucial for the health and well-being of the Rohingya refugees. However, this needs to be done with consultation and consent of the refugees to keep their displaced village communities intact and maintain contact with the broader Rohingya refugee community.

The Bangladesh navy and Chinese construction crews have prepared the as yet uninhabited island of Bhasan Char for the transfer of 100,000 refugees from the Cox’s Bazar area, and Bangladesh has indicated that transfers to the island will begin in September. However, the flat, mangrove and grass island, formed only in the last 20 years by silt from Bangladesh’s Meghna River, does not appear to be suitable for the accommodation of refugees. Experts predict that Bhasan Char could become completely submerged in the event of a strong cyclone during a high tide. In addition to Bhasan Char’s environmental failings, housing refugees there would unnecessarily isolate them, and if they were not allowed to leave, it would essentially become an island detention center.

Bhasan Char does not appear to be a suitable relocation site for refugees for a host of reasons: 1) it is not sustainable for human habitation; 2) it could be seriously affected by rising sea levels and storm surges; 3) it likely would have very limited education and health services; 4) it would provide extremely limited opportunities for livelihoods or self-sufficiency; 5) it would unnecessarily isolate refugees; 6) the Bangladeshi government has made no commitment to allow refugees’ freedom of movement in and from Bhasan Char; 7) it is far from the Myanmar border; and 8) the refugees have not consented to move there.

The Rohingya refugees who spoke to Human Rights Watch expressed gratitude to the people and government of Bangladesh. That goodwill could be squandered, however, if government security forces pressure refugees to go to Bhasan Char, putting their lives in danger.

Bhasan Char is not the only relocation option. There are six feasible relocation sites in Ukhiya subdistrict totaling more than 1,300 acres that could accommodate 263,000 people. These sites are situated in an eight kilometer stretch due west of the Kutupalong-Balukhali Expansion Camp between the mega camp and the coast. As such, these sites are within the containment area the government has designated to limit free movement of refugees.

Another challenge facing Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh is the lack of recognized legal status, which puts them on precarious legal footing under domestic law. All the new arrivals are officially registered as “Forcibly Displaced Myanmar Nationals,” a designation that denies their refugee status and any rights attached to that status. This makes them more vulnerable to denial of freedom of movement, access to public services, education, and livelihoods, as well as to arrest and exploitation. However, as a party to core international human rights treaties, Bangladesh is nevertheless obligated to ensure all persons within its jurisdiction, including refugees, retain access to fundamental rights.

The refugees interviewed privately by Human Rights Watch all expressed their preference to go back to Myanmar, but only when conditions allowed them to return voluntarily: citizenship, recognition of their Rohingya identity, justice for crimes committed against them, return of homes and property, and assurances of security, peace and respect for rights.

“Creating a conducive environment for return rests with Myanmar, not here,” Bangladesh’s Cox’s Bazar-based refugee relief and repatriation commissioner, Abul Kalam, told Human Rights Watch. “We cannot force them back.”

Although not a party to the 1951 Refugee Convention, Bangladesh has upheld its customary international law obligation to keep the border open to fleeing Rohingya refugees and acted to accommodate and meet the humanitarian needs of hundreds of thousands of desperate refugees fleeing crimes against humanity. More than nine months since the crisis began, it remains an emergency situation, one not likely to be resolved anytime soon.

Human Rights Watch calls on the government of Bangladesh to establish readily accessible, hard-structured cyclone shelters to enable evacuation of refugees in Kutupalong-Balukhali mega camp to safer areas. The authorities should relocate refugees from the mega camp to smaller, less densely packed camps on flat, accessible land in Ukhiya subdistrict. It should immediately terminate plans to relocate Rohingya refugees to Bhasan Char unless and until independent experts determine that it is suitable for the accommodation of refugees, and until the government ensures that refugees who consent to relocate there will be allowed freedom of movement on and off the island. Bangladesh should register the Rohingya who have fled Myanmar as refugees, ensure access to adequate health care and education, and enable greater freedom of movement to engage in livelihood activities outside the camp.

The Myanmar government bears responsibility for the Rohingya refugee crisis and resolving it will necessitate fundamental and durable changes in Myanmar. The government will need to ensure full respect for returnees’ human rights, equal access to nationality, and security among communities in Rakhine State as a precondition for voluntary repatriation in safety and dignity.

In the meantime, donor governments and inter-governmental organizations should be genuinely and robustly involved, both in supporting Bangladesh to meet the humanitarian needs of all Rohingya refugees – particularly by funding the humanitarian appeal for the Rohingya humanitarian crisis – but also by applying concerted and persistent pressure on Myanmar to meet all conditions necessary for safe, dignified, and sustainable return of the Rohingya refugees.

Download full report HERE.

Announcements

28 February 2025

Asian NGO Network on National Human Rights Institutions , CSO Working Group on Independent National Human Rights Institution (Burma/Myanmar)

Open letter: Removal of the membership of the dis-accredited Myanmar National Human Rights Commission from the Southeast Asia National Human Rights Institution Forum

Progressive Voice is a participatory rights-based policy research and advocacy organization rooted in civil society, that maintains strong networks and relationships with grassroots organizations and community-based organizations throughout Myanmar. It acts as a bridge to the international community and international policymakers by amplifying voices from the ground, and advocating for a rights-based policy narrative.